Spotlight: Elsey Come Home by Susan Conley

/From the widely praised author of Paris Was the Place—a shattering new novel that bravely delves into the darkest corners of addiction, marriage, and motherhood

When Elsey’s husband, Lukas, hands her a brochure for a weeklong mountain retreat, she knows he is really giving her an ultimatum: Go, or we’re done. Once a successful painter, Elsey set down roots in China after falling passionately for Lukas, the tall, Danish MC at a warehouse rave in downtown Beijing. Now, with two young daughters and unable to find a balance between her identities as painter, mother, and, especially, wife, Elsey fills her days worrying, drinking, and descending into desperate unhappiness. So, brochure in hand, she agrees to go and confront the ghosts of her past. There, she meets a group of men and women who will forever alter the way she understands herself: from Tasmin, another (much richer) expat, to Hunter, a young man whose courage endangers them all, and, most important, Mei–wife of one of China’s most famous artists and a renowned painter herself–with whom Elsey quickly forges a fierce friendship and whose candidness about her pain helps Elsey understand her own. But Elsey must risk tearing herself and Lukas further apart when she decides she must return to her childhood home–the center of her deepest pain–before she can find her way back to him. Written in a voice at once wry, sensual, blunt, and hypnotic, Elsey Come Home is a modern odyssey and a quietly dynamic portrait of contemporary womanhood.

Excerpt

Chapter One

About a year ago my husband handed me a brochure for a retreat in a nearby mountain village. We were standing in our Beijing kitchen while the girls played make-believe dog at our feet. The brochure was more like a handmade pamphlet—four pieces of white computer paper folded in the middle and stapled three times along the crease. There was a grainy photo of a cement terrace on the cover, and a more alarming photo of people sitting in a room with their eyes closed, and text under the photos that explained something called “a day of silence” and yoga and the chance for participants to reinvent themselves. My husband, Lukas, told me these things would make a good week’s vacation for me, and he smiled while I looked at the photos, but it was a distant smile.

He went back to his bowl of rice, and I pressed myself against the edge of our stove until my lower back hurt, and I felt so lonely I almost cannot say. I knew if I went to this village, the week would pass slowly and I’d be changed, and that this was the point of him sending me there, but also that Lukas and I might not ever find each other again.

I’d recently had a small surgery with my thyroid, and the Chinese doctor said I would get better, and he was right and so I did. But I’d been in and out of hospitals that previous winter, and when I was home I lay on the couch while Lukas and the girls continued on with their lives. Myla was eight. Elisabeth was seven. They sweetly cleared their plates and cups from the table and put them in the dishwasher upside down. Lukas often read the bedtime stories, and I saw he was trying hard to help me, but that I wasn’t needed as much as I thought, and that I must learn how to be a different kind of mother. A different kind of wife. It still feels like that now while I write this. That I cannot go back to the way I was before.

I will also say that when Lukas handed me the brochure in our kitchen I didn’t know how to be in a marriage. A real marriage. I’m not sure he did, either. He was from Denmark and had lived in Beijing for fifteen years, making music, and he stormed about the government’s crackdown on journalists and rising nationalism, but I’m not sure he’d ever learned how to really listen.

The day before I left for the retreat we took the girls downtown to a Japanese restaurant called Hatsune, which is lined with dark wood and tatami and serves large ceramic bowls of ramen and a sweet, sticky white rice Myla and Elisabeth love. After the rice got served I told the girls I was going away for the week to a tiny village called Shashan, and they stared at me with their grave eyes and clouds of hair. Then the fresh lemon sodas arrived, and neither of them seemed to register my announcement again, even though it was a rare announcement because I hardly ever left them. They played tic-tac-toe with a small pad of paper and pens I’d brought in my bag, and got up to look at the oversized catfish in the aquarium.

During the meal Elisabeth politely asked for a mayonnaise sandwich even though Hatsune was her favorite restaurant in Beijing, and she has always hated mayonnaise and refused to eat anything with mayonnaise on it. When we got home, Lukas made her the mayonnaise sandwich, and I stayed with her in the kitchen while she ate it so Lukas could put Myla to bed. There are two steel stools with black matte leather seats at the end of the stone counter, and Elisabeth and I sat on these while she ate the whole sandwich, which became, I think, a kind of statement. Her long hair was tucked behind her ears, which saved it from getting in the mayonnaise, and she didn’t say anything else about my leaving for the mountains.

Chapter Two

When Elisabeth was done with the sandwich, I walked her to her room and she lay on her bottom bunk, and I hadn’t closed the curtains yet, so we could still see the skyline and the enormous Chinese TV building so famous people come from around the world to look at it. From our apartment it resembles a pair of gray pants. So big I cannot even begin to explain it, and Elisabeth is often in awe of this building. Me too. How could people even get inside that building?

We live downtown in a high-rise near the most gigantic train station. When we moved here just before Myla was born, I circled the train station on my map with indelible marker so when I got lost I could take out my map and try to find my way home.

Elisabeth rolled over on her stomach in the bed. “Imagine,” she said, “if you spoke wolf language. I mean really spoke it. Would you live with the wolves and leave your mother and father and never come back?”

She often asked me questions that involved leaving our family, and I didn’t want her to leave our family, and I told her this. Then I said, “Living with wolves would be exciting, and if you didn’t like it you could come back.”

She looked at me like this was an acceptable answer, and I felt I’d passed a test, which is how I often felt with Elisabeth. Like she was administering a series of small philosophy exams, which were essential I pass in order to be allowed to continue being her mother.

I stood and pulled the blue curtains closed. This was more curtain than I’d encountered in a room, because the picture window was that big. A sliver of light from the noodle house below cut through the gap between the curtains and fell on the rug, and Elisabeth often said it looked like the scar on Harry Potter’s forehead.

The rug was hard like turf because it was laid down over concrete, and I’d never seen so much concrete before in my life until I lived in China. Elisabeth asked me what God I believed in, and I’m not sure if this interrogation was already happening before I had the thyroid surgery, but it threw me, because I often asked myself the same question privately. I told her I believed in the God of Family. “You know. The God who keeps families together forever and ever, so they are never apart.” Lying was the thing she disliked most of all, but I used to believe it was a way to spare her.

“But what do you really believe in, Mom?”

I smiled for how well she knew me. She’d already changed into the blue sweat suit, because she required being fully dressed for school before she got out of bed in the morning, and I no longer argued with her about this. But it was quite hot in her room and her face was flushed.

“Because I believe when you die,” she said, “you go to heaven for thirty years and then you come back as a cheetah because you want to be that fast.”

“Okay. Well, what I believe in is my love for you. That’s what I believe.”

I was trying to calm her mind so she’d be able to sleep. I could still mostly get away with naming my emotions for her explicitly. Maybe they were emotions I couldn’t fully name with my husband. I feared once she got just a little older, it would be over and she wouldn’t let me speak these things any longer, which has turned out to be mostly true. But there was this sweet time when I got to say them, and it has meant a lot.

Sometimes the streetlights outside her room flickered, and they began doing it then—blinking on and off, and the light landed on the strip of rug underneath the gap in the curtain and made the shapes. “Let’s go to sleep now,” I said.

I wanted her to sleep so I could pack. I also wanted a drink. I’d begun wanting one every night that winter after I put the girls to bed. I can’t fully account for it, but I will say that it didn’t feel like anything really happened during those days until I had a drink. I wasn’t painting, and I wasn’t with the girls doing what some people call parenting, because I was so often on the couch after the surgery. The girls tested me, and I tired more easily. They were still young and wanted things from me, as they should. Food and kisses. I gave them all of this.

I’d certainly drunk before my surgery, but never with intention. And now I thought I might be sicker than the doctors had said, and I was too in a hurry to return to my private conversation with the world about this. It sounds odd. My fear. I was slowly getting better but I couldn’t stop the worries, and I thought it was a secret how afraid I’d gotten.

You hear it and don’t understand when women say they lost themselves, because it seems overdone, and there are four hundred million people in China living on a dollar a day, so cry me a river.

There’s a small, fetid canal outside our apartment where a handful of old men from the hutong fish for carp and catfish. Elisabeth became fixed on these men out our window and often made us walk to the canal to watch them. She was a willful child like this and could take up a lot of the day, but I had no excuse for not painting in the two years leading up to my illness. What I will say is that I couldn’t understand how to be obsessed with my children and obsessed with my painting at the same time. I thought both called for obsession. I had a narrow view of the world and I was younger then, but really I was naïve.

Excerpted from Elsey Come Home by Susan Conley. Copyright © 2019 by Susan Conley. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Buy on Amazon | Barnes and Noble

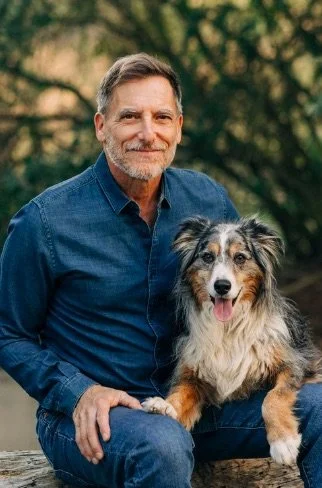

About the Author

SUSAN CONLEY is the author of the novel Paris Was the Place and The Foremost Good Fortune, a book that won the Maine Literary Award for memoir. Born and raised in Maine, her writing has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The Paris Review, and Ploughshares. She has been awarded fellowships from the MacDowell Colony, the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, the Maine Arts Commission, and the Massachusetts Arts Council. She spent three years in Beijing with her husband and two sons before moving back to Portland, Maine, where she currently lives. She teaches in the Stonecoast Writing Program at the University of Southern Maine.