Spotlight: It Is What You Make of It by Justin McRoberts

/Paperback : 208 pages

Justin McRoberts dares you to move beyond “it is what it is” thinking and become an agent of love and redemption in your household, neighborhood, and workplace.

“It is what it is”—a common phrase you hear and maybe even say yourself. But the truth is that there is not one square inch in the whole domain of our human existence that simply is what it is. Justin McRoberts invites you to embrace a new mindset: it is what you make of it.

With warmth, wisdom, and humor, McRoberts shares key moments from his twenty-plus years as an artist, church planter, pastor, singer-songwriter, author, neighbor, and father, passing on lessons and practices learned about making something good from what you’ve been given rather than simply accepting things as they are.

Thought-provoking but actionable, It Is What You Make of It declares that love doesn’t just win, mercy doesn’t just triumph, and light doesn’t just cast out shadow. Rather, such renewal requires the work of human hands and hearts committed to a vision of a world made right (or at least a little better). When we partner with God in these endeavors, we love the world well and honor the Creator in whose image we are made.

We will not be remembered for who our parents were or where we were born or what our socioeconomic circumstances were. We won’t be remembered for our natural talents and strengths or the opportunities we were given or the challenges we faced. In the end, each of us will be remembered for what we made with what we were given.

Excerpt

FIVE

Everybody Hurts, Everybody Matters

In the fall of 2010, I started the largest and most time- consuming and energy-sucking creative project of my life up to that point (and, God willing, ever). I didn’t know that when I started it. I just thought I’d throw together a few good ideas and have some fun! Then, I’d invite a small team of people to join with me, and the fun would be multiplied to partylike status. Only, this party was three people working way too many hours for nowhere near enough money while I disintegrated into the worst version of myself anyone at the “party” could have imagined.

Cue Richard Wagner–oriented party playlist.

The project was a combination of letter writing and essays and music and lyrics and visual art and documentary-style video and stress and passive aggres- sion and regular aggression and also personal reflections on relationships. Thematically, it was a celebration of community and a record of what my friends and family had made out of the circumstances and relationships God had gifted us. Eventually released in 2012 and called The CMYK Project, it turned out alright as a project. Sadly, it cost me a dear friend along the way.

One of the final phases of The CMYK Project involved the printing of a book. Actually, that’s only partially true; it was two books. Actually, that’s only partially true as well; it was really the same book in two formats. Somewhere in the process, we (and by “we” here, I mean “I”) decided on printing two versions of the same book; one version was just a regular-ole book with text on paper. The other was a two-hundred- page, full-color extravaganza featuring artwork and photography and interviews (which I didn’t mention in the description above, just like I didn’t mention it to my team when we were working on it) along with letters and essays. It’s probably also worth noting that we released the music on three separate EPs with three different covers and then selected a few songs from each of those EPs, rerecorded those songs, and tacked on even more songs to create a fourth musical aspect to the project—a full-length, full-band, studio-recorded album. So what we produced was . . .

a four-CD, twenty-five-song collection, a text-only book,

a full-color book,

three physical art installations by different artists in different cities,

video interviews with each of the visual artists, transcribed, printed versions of each of those inter-

views, and the gradual, tragic disintegration of every relationship.

Yeah, yeah, yeah. I know . . . It. Was. A. Lot.

The real fun begins with knowing that I’d never done anything like that before. In fact, I’d never made a book before, which was probably the most straight- forward part of the entire project. To make that portion of the project simpler and easier on us (and by “us” here, I mostly mean “me”), my art director and I sub- mitted the book-printing process to a large, reputable printing company. Having done what we thought was all the heavy lifting (writing, designing, formatting, arguing, walking away, and then returning to the same argument . . . blah, blah, blah), all that was left was to upload the book files; make the few, small adjustments we’d probably need to make; and then dance victori- ously as the book (along with every other aspect of the project) found its way into the hands, hearts, and minds of readers .

Three days after the first upload, we got a notifi- cation that there were things in need of fixing. Like I said, we expected this, and while the list of correc- tions was quite a bit longer than we’d anticipated, we happily fixed the book and uploaded it again, thrilled to be done with this massively too-big and costly, and also ridiculous to the point of being beyond description, project.

Three days after that, the printer responded a sec- ond time with a list of errors, several of which we were certain we’d fixed. So I called the printer’s customer ser- vice number . . . and I wasn’t kind. Not even a little bit. I was tired, and I felt that being tired somehow excused me from being kind. After feeling like I’d sufficiently communicated my frustration and disap- pointment, I hung up, and we dove into our third round of edits and fixes.

Then there was a fourth, and then a fifth, and a sixth, and eventually, the same two things started happen- ing every three to four days:

We received the same set of twenty-five notifications and necessary changes.

I ended up on the phone with customer service.

Over and over and over for weeks and weeks and weeks.

The only things that seemed to change were my level of frustration and the depth of insult I was there- fore prepared to dole out over the phone to the agent I spoke to.

This went on for twelve rounds.

Quick math: twelve rounds times three business days per round (which means we’re not counting weekends) means six-plus weeks, which, divided by seven days per week, factoring relational stress and a dwindling supply of bourbon = YIKES!!!

When that twelfth email came from the printer, I stared at my computer screen blankly until my art director spoke up. “I think I’ll call this time, okay?” said Gary. “I’m not as angry as you are.”

I left to run a few errands while he called the printer. When I got back, Gary told me he’d worked it all out. I wanted to know if “working it all out” meant he’d murdered anyone. He said no, which was slightly dis- appointing but probably for the best. What he meant by “working it all out” was that he’d asked to speak with a supervisor, just as I had. And just as had happened when I’d called, Gary was told they didn’t have supervisors. But then, instead of losing his cool and insulting the person on the other end of the call (my strategy), Gary calmly described our situation and history in detail and kindly but firmly asked who he should be talking to.

“You need a specialist,” the agent told him.

In eleven previous calls, I’d never even heard the word specialist much less been given the option to speak to one.

Gary said he held the line and was connected to someone we will call, for the purposes of this story, “the Specialist.” Gary described our situation, and the Specialist said she thought it was “really odd.” Gary assured her he was aware of how odd it was and then asked what we needed to do. The Specialist asked Gary to upload the file again.

“With all due respect,” Gary replied, “we’ve uploaded the file a dozen times now.”

“I can see that,” said the Specialist. “This time, I’ll stay on the phone with you and wait for it to hit our system. Then we can look at the file together.”

Ten minutes later, Gary and the Specialist were looking at the file together.

“Is your file supposed to be five-by-eight or six-by-nine?”

“It should be six-by-nine.”

The Specialist paused and then asked Gary if she could call him back. Twenty minutes later, she called back and told Gary what was actually going on. It wasn’t that their system had a glitch or that our file was corrupt or even that we were doing something tech- nically wrong.

It was much worse and far weirder than any of that. During one of the early phone calls in the editing process, I’d said something pretty horrible to one of the technicians. In turn, he’d reset the specs on our project from six-by-nine (which was correct) to five-by-eight, so that every time we uploaded the file, it would trigger dozens of warnings and be rejected. The technician had sabotaged our project. That’s a pretty horrible thing to do to someone. But he did it because I’d been horrible to him.

Now here’s what’s really funny (and by “funny” I mean painfully ironic and related to my social inepti- tude): the full title of the CMYK Project—the book plus three EPs plus full-length LP plus visual art plus video plus other book—was CMYK: The Process of Life

Together and was promoted as “a celebration of life in relationship.” It was chock-full of stories and anecdotes about getting along with and loving other people, par- ticularly where there were differences of opinion and experience. It was a project about my own process of learning to love people the way Jesus loved people.

So . . .

Can you imagine being the tech on the other end of the phone, staring at a chapter about the uncondi- tional love of God while the author of that chapter calls you names? Perhaps you’d think the love and kindness described in those pages weren’t for you. And if I’m honest, I certainly wasn’t offering them to that cus- tomer service agent, because in my mind he wasn’t a person but an instrument. I talked to him the way I talk to the car that won’t start or the software that freezes. His value was entirely predicated on how useful and helpful he was to me.

My encounter with that tech reminds me of one in the Gospel of Mark: the one about a woman whose body was healed when she simply touched the clothes Jesus was wearing. It’s a remarkable story in a lot of ways. First of all, that was quite an ensemble Jesus had on, right? I’ve got a few favorite shirts, but none of them have mystical healing properties. More significantly (and less jokingly), I am captivated by the choice Jesus made to stop and talk with the woman who touched “the hem of his garment” (Matthew 9:20). Because the way he handled the moment says far less about the clothes he had on or even his power to heal and far more about how important and valuable she was to him.

As the writer of Mark told it, a man named Jairus, whose daughter was dying, went to find Jesus to ask for help. Jesus was up to other things at the time, but he changed course when Jairus asked him to heal his daughter. That part makes sense to me. Jairus led a syn- agogue, which made him a big deal in social, political, and religious circles. Helping Jairus presented a legit- imate opportunity to heighten Jesus’ profile, prove a few folks wrong, and “get the message out,” as it were. But as Jesus was following Jairus back to his home, the trajectory of the story changed.

And a woman was there who had been subject to bleeding for twelve years. She had suffered a great deal under the care of many doctors and had spent all she had, yet instead of getting better she grew worse. When she heard about Jesus, she came up behind him in the crowd and touched his cloak, because she thought, “If I just touch his clothes, I will be healed.” Immediately her bleeding stopped and she felt in her body that she was freed from her suffering.” (Mark 5:25–29)

Jesus then asked about who touched him, which a few of his friends found a bit silly, seeing as though there was a whole mob of people jostling about and bumping into one another. But to Jesus (and this is the part that gets me), this woman wasn’t just another per- son in the crowd. Which is why I absolutely love the way the writer of Luke wrote about this same story. As he retold it, when Jesus asked about who touched him, she tried to stay hidden but eventually conceded that “she could not go unnoticed” (Luke 8:47).

How good is that?

“She could not go unnoticed.”

Jesus stopped, and along with him, the whole crowd that had been following him. I don’t know how long their conversation went on, because none of the writers who captured this moment provided that detail. But apparently it was long enough for Jesus to hear a lot of this woman’s story. She’d been sick and bleeding for twelve years with multiple medical failures along the way. The other thing the story makes clear is that Jesus was invested enough in the conversation that someone else had to interrupt him and let him know Jairus’s daughter had died.

Now, it’s significant that, once Jesus finally did arrive, he assured the people in Jairus’s household that, despite appearances, he had things in hand and could still heal Jairus’s young daughter. That says to me that Jesus had enough confidence in his ability to do the work he’d committed to that he could pause for a moment along the way and turn his full attention to a person he’d met so that “she didn’t go unnoticed.”

That customer service agent wasn’t just another per- son along the way, though I treated him like he was. Since the CMYK Project, I’ve learned that . . . the customer service agent helping me sort out font problems during manufacturing, the Apple Genius Bar employee helping restore my lost data, my web developer, the barista or bartender serving me while I write, the UPS or FedEx driver delivering proofs, the neighbor whose dog pops over to play ball while I’m editing, the dog herself who wants to pay ball . . .all these people are actually people (except the dog, who is not a person but thinks she is, so we’ll keep her on the list). They are, each of them, beloved ones of God with dreams and hopes and problems and opportunities and relationships and needs and gifts and strengths.

They are the kinds of people worth making great work for. Which also makes them the kinds of people worth stopping great work for, whether or not they’re directly part of that work process or not.

They aren’t stepping-stones on my path to success. They aren’t cogs in the wheel of my productivity. They aren’t part of my “system.”

Even (and especially) if they’re part of my team working to complete a project.

Remember a moment ago when I asked you to imagine being the technician on the other end of the phone, staring at an entry about the unconditional love of God while the author of that page yells at you and calls you names? Well, let’s take that one step further, shall we? Because that’s where the deeper learning les- son was for me.

Imagine being my art director, Gary, who took on that final phone call to put the project back on track after I’d derailed it with my anger. Imagine working for nearly two years on a project ostensibly celebrating the unifying love of God for people while watching your partner and project leader verbally abuse customer ser- vice agents over the phone and then carry that anger around the office every day. Maybe you’d lose respect for that person. Maybe you’d have a hard time trusting them as a leader or a friend. Maybe you might even decide that was the last time you’d work with that per- son or anyone like them if it meant being treated that way or being party to treating others that way.

You see, what I know now is that how I treat the people I work with . . . nope. Let me fix that:

What I know now is that how I love the people I work with and for and around says ten thousand times more about who I am than any project or job or end result, regardless of its effectiveness, beauty, impact, or market success. I’d rather make garbage work while honoring and maintaining great relationships than cre- ate bestselling work while becoming the kind of person nobody wants to be around.

It was and is the love in Jesus that was and is the source of healing, whether on the street in a crowd or in the back room of a powerful social figure—which is to say, Jesus was the same person wherever he went.

I want to live like that.

I want that kind of love to dictate the way I work. The way I’d addressed the young man at the print-ing agency had almost nothing to do with his job or position or the fact that I didn’t personally know him; it had everything to do with me and my character. Yes, the professional distance between us made it easier for me to be unkind, but the capacity to dehumanize some- one and use them for my own purposes was in me from the start. And here is something true: I don’t get to (and shouldn’t want to) make anything out of someone else’s life. That’s not my job. My vision isn’t big enough for your life. That’s God’s job. Only divine hands can make something out of a human life without belittling, stifling, and minimizing that person in the process.

About four years after that first book came out, my third book hit the shelves. It was a book of prayers I’d collected from my own practice, born out of trying to live more intentionally. Among them was the prayer I wrote shortly after the completion of The CMYK Project. It reads,

May the work I do never become more important to me than the people I get to work with or those I’m working for.

Taken from “It Is What You Make of It” by Justin McRoberts. Copyright 2021 by Justin McRoberts. Used with permission from Thomas Nelson.

Buy on Amazon Kindle | Audible | Paperback

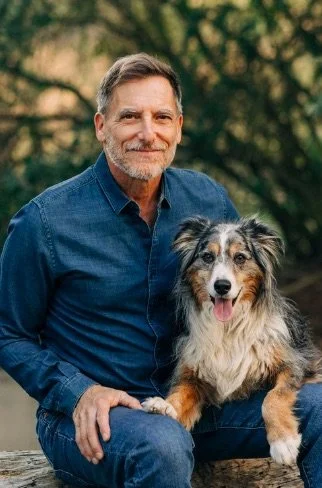

About the Author

Justin McRoberts lives in the Oakland–San Francisco Bay Area with his wife, Amy, and two children. He is the author of four books, including Prayer: 40 Days of Practice and May It Be So: 40 Days with the Lord’s Prayer. Justin’s sixteen albums and EPs have gained him a faithful audience among listeners nationwide since 1999.

Justin leans on his over twenty years in the arts and ministry to mentor and coach artists and pastors in person as well as over video calls. He is also the host of the podcast @ Sea with Justin McRoberts and co-founding pastor of Shelter-Vineyard Church Community in Concord, CA. Justin regularly travels to speak at churches and colleges, as well as leads retreats for ministry staff, college students, and young adults.

Connect with Justin: Website | Facebook | Twitter | Instagram