By the New York Times bestselling author of Mother, Mother and Smashed comes a propulsive new thriller: the story of a desperate and devious woman who will do anything to give her family a better life

Gracie Mueller is a proud mother of two and devoted wife, living with her husband Randy in upstate New York. Her life is complicated by the usual tedium and stressors—young children, marriage, money—and she’s settled down comfortably enough. But when Randy’s failing career as a real estate agent makes finances tight, their home goes into foreclosure, and Gracie feels she has no choice but to return to the creatively illegal and high-stakes lifestyle of her past in order to keep all that she’s worked so hard to have. Gracie, underneath all that’s marked her life as average, has a lot to hide about where she’s from, who she is, and who she’s been. And when things inevitably begin to spin out of her control, more questions about the truth of her past are raised, including all the ones she never meant to, or even knew to, ask.

Written with the style, energy, and penetrating insight that made her memoir Smashed a phenomenon, Koren Zailckas’s next novel confirms her growing reputation as a psychological novelist that can stand up to the best of them.

Excerpt

Chapter One

The desk clerk walked behind me with purpose, adjusting the name tag on his lapel.

Poor casting, I thought when I saw his reflection in a mirrored alcove. His expression seemed to be aiming for stern, but his pimpled chin gave him a look of teen angst. If I’d seen him looking as cheesed-off anywhere but there--at the Odell Resort and Spa, described by Forbes as “a modern chateau nestled at the foot of the Catskill Mountains”--I would have guessed he’d failed maths or been friend-zoned by a girl.

“Hi there. Ma’am?” He was so square, you could wage a game of chess on him, and I reckoned he had the sort of bohemian parents that were a regional trend. Some failing authority figure had left him with no other course of rebellion. When sex, drugs, and a vegetarian diet are the norm, only steady employment has shock value.

“Looking for something?”

“Mum-eee.” Kitty pulled the belt of my white cotton robe. My hair was swept over my left breast, where the hotel’s logo should have been.

“Darling, please don’t tug.”

The robe, a gift from my first husband, Oz, was my last bastion of luxury. A few years earlier, it had been my Christmas present. It was the last thing Oz gave me before he was indicted for fraud.

Fitz, who was five going on thirty, echoed: “Kitty. Mum said don’t tug.”

I had planned that afternoon for Fitz in particular. He’d had his first ever swim in Cannes, surrounded by superyachts, but he’d grown sadly accustomed to the Catskill Community Pool, where the deck chairs are spattered with bird shite.

“You’re so very kind,” I told the clerk. “We’re meeting friends.”

In general, I could count on my accent to give me an air of refinement.

Back in my native Britain, people heard culture clash when I spoke. The British associated my cut-glass accent with grasping or some variant: putting on airs. I’d grown up striving for the upper classes’ attention to h’s and t’s, but fell into the dirty habit of elongating my vowels so that I might fit in with my working-class mates.

But in the States, there was only one type of English accent. Upstate New Yorkers assumed I was educated and worldly, cleverer than they were. Shopkeepers praised my pronunciations (“vitamins” or “oregano”) as though I were a rare, exotic vocalist. The other mums at Fitz’s play-school treated us as though we ate cucumber sandwiches for tea and hoarded money offshore.

But this young man seemed impervious to my BBC English. “I can look up your friend’s room number at the front desk.”

I pored over my mobile’s blank screen, pretending I’d received a new message. “Oh. It appears our friends have been waiting by the pool for thirty minutes. Shall we go meet them, Kit? Fitz?”

Just then, my phone legitimately vibrated. It was my current “husband,” Randy, calling from Florida.

I gestured to the clerk: One minute, sorry.

“Hiya, Randy, you all right?’

“--cie. Hi. Can you hear--e?” His voice was breaking up. Either a result of the looming mountains or the resort’s thick walls.

I slowed the children near an ebony sideboard and watched them shuffle travel brochures at twice the speed it took me to return them to their proper piles.

“I hear you. But it’s not a brilliant time. We’re late meeting friends.”

“Where?” he asked, a question that was shorthand for: How much will it cost?

I turned my back to Fitz. “The YMCA,” I said softly.

“How’s it going with your Social Security number?”

The question always hit me like a punch to the solar plexus.

“Look, Mummy! A choo-choo!” Kitty said. Leaflets for a railway museum rained like war propaganda across the lobby’s pristine floor.

“Going well.” I laid a hand on Fitz’s elbow--stopping him seconds before he wiped his nose on a silk sofa arm.

“So you got it?” Randy asked.

“Getting it.”

“I just don’t understand why it’s taking so long. Or why you didn’t request a social when you applied for your visa.”

“It was an oversight.”

Two years ago, I’d applied for the green card that would have entitled me to a social, but the letter that arrived from the Department of Homeland Security informed me that the documentation I’d submitted was incorrect. Rather than going back to Britain, I’d faked an immigration interview at Twenty-Six Federal Plaza on a day when I knew Randy had a real-estate closing. I took a bus to Manhattan, treated myself to a steak at Mark Joseph, and returned to Catskill, six hours later, with a story that held him over until a forgery-mill website delivered my novelty resident card. I’d waited until the morning after his bachelor party to show it to him, rightfully suspecting he’d be too hungover to notice the smeary blotches under the laminate.

The phony green card wasn’t even the biggest lie I had brought into our marriage. On paper at least, I was still married to Oz, because filing for divorce would have created a paper trail, and police wanted me for my role in his bogus property deals.

Randy, still on the phone, shifted into estate agent mode: “Gracie, you need your own credit line. Now. That way, if we need to borrow money, no one will know we missed a few mortgage payments.”

“A few? You said last month was the first time.”

He lowered his voice. “Gotta go. A lead just walked in.”

I hung up, herded the children through the sliding-glass doors, and slammed headfirst into the day’s crippling humidity. It was 2010, the hottest summer on record in New York. The gray sky, unexpectedly bright, seared my eyes. Waves of hot exhaust rippled across the parking lot.

Fitz urged Kitty to hold on to his back and run in tandem. “Come on! Be my jet pack!”

“Careful,” I warned, as the game almost always ended in skinned knees.

“We are being careful,” Fitz said with a look that accused me of needless drama.

The pool gate squealed on its hinges, and a few women rubbernecked at the sound.

I had never put much stock in vanity, but I wondered what those freshly waxed and mud-bathed ladies saw when they look at me.

Had they met me at Guildhall, my dramatic arts college, they would have seen a loosely defiant young woman with a burst nest of ginger curls and an attitude that said drinking cider on wet lawns was just as educational as reciting Shakespeare. I sang in a twee pop band and rolled immaculate joints. My fashion choices were daring and my mates even more so: hot pants and kimono, with a crusty, bisexual chap from the Royal College on my arm. I wouldn’t say strangers instantly noticed when my younger self walked into a room, but I had a certain heady trifecta: ambition, charisma, and a fair bit of luck.

By my early thirties, Fitz was in a fashionable sling across my chest and dreams of acting in the West End were a distant memory. But even then, I’d retained an air of sophisticated rebellion. I wore Peter Pan collars with black leather miniskirts. I peppered my speech with French and obscenities. I could act at ease in fifteen-bedroom country houses and even help Oz woo investors for Turkish condominiums he didn’t own.

Then of course, there was the indictment and the separation, and my mid-thirties found me in America, “married” to Randy, a top-earning Realtor. Too old to play the ingénue, I took on the role of the pampered housewife instead. Randy supported me by flipping houses, leasing out his income properties and closing on two or three real estate deals every week. And I lived a life of relative leisure, organizing menus and playdates, collecting Le Creuset cookware and Jo Malone perfumes, getting pregnant with Kitty. Then, just when I didn’t lack for anything, the real estate market collapsed, and life demanded austerity measures.

If anyone noticed me that day at The Odell, it was apt to be in pity, not awe. Having quit the salon, my hair was reaching red-gray. Without a gym membership, my body was slackening at the midriff and hips, widening and collapsing like a carnival tent after the fun’s over and the punters have gone home.

I panned the poolside, taking in our chaise options. There were no friends expecting us, of course. I’d planned on letting Fitz down gently, with a little white lie about how something came up: car troubles, stomach illness, someone had drunk a bad juice box or stuck their finger too far up their nose. “Caleb’s mum texted.”

That said, I had neglected to pack a lunch, so it was well worth making myself friendly.

Near the shallow end, there was a pensioner who looked promisingly lonely. She was sipping cucumber water in an Indian-style dupatta, wearing her wealth like the facelift scars around her ears. I paused in front of her and pretended a deep yawn, which she mirrored with subconscious empathy. But then, she glanced at Kit and Fitz with a look of child-hatred, so I carried on down the line of chairs, searching.

We walked by a toddler who was clutching a tennis ball as she trailed her Caribbean nanny. “Do you want to be in the shade?” the woman asked, loudly dragging a chair.

We passed a trophy wife who was describing her lunch to another: “I had the noodle bowl, and it was ah-mazing. Instead of pork, I had them throw in an egg and a whole bunch of veggies.”

There, I thought.

On the far side of the kiddie pool, a pair of yummy mummies discussed their children’s class assignments for the coming school year while a third woman, on the periphery, pretended not to eavesdrop.

“Who does Izzy have again?” one woman asked. “Ah well. All the third-grade teachers are a win-win. I heard Layla’s in that class too. And Willow. Oh, and Ollie Guerra. His parents just bought the Dylan house.”

When the onlooker’s phone chimed, she quit spying and rifled through her hideous charity tote bag, which was printed with the slogan kindness is always in fashion.

I nudged the children closer and sat as near to her as possible without seeming too keen. Leaving an empty sun lounger between us, I watched her divide her attention between her mobile and the supervision of an Asian girl in pink goggles that matched her pineapple-print suit. She was wearing the sort of expensive-looking Panama hat that Manhattanites wore when they came up for the weekend. But I caught a whiff of something gauche and suburban as well: her over-baked tan looked sprayed on, whereas the city mothers kept their skin liberal-pasty.

She was proud, not scolding, when she unknotted a bit of hair from her child’s earlobe: “Those earrings are probably not good pool earrings. Because they’re grandma’s pearls. Do you know what I mean?”

I set to work, delicately removing Kitty’s dress. No sudden movements. Nothing attention-seeking. Just enough motion to make the woman gradually aware of me.

Goggles in hand, Fitz galloped toward the pool.

“Walk, please,” I called. Then, to Kitty: “I’d like you to wear this hat so your lovely face doesn’t burn.”

“I don’t want a hat!”

In my peripheral vision, my mark pecked away at her phone with a manicured index finger.

I sighed a little louder than necessary. “Last time we were here, you sizzled, Sausage. I felt like the worst mummy of all time.”

The woman glanced up, making me wonder which part of what I said had captured her interest. A sense of superiority, maybe. Women are moths to the flame of others’ failures.

“Your mommy’s right,” she told Kitty. “Last year, at Long Beach Island, I sent my Gabby to the beach in pigtails and forgot to sunscreen the part. Her scalp blistered. She looked like she’d had hair-transplant surgery.”

“Is it all right to shift over?” I asked, already moving my bag to the empty chaise between us.

“Sure,” she said in a falsetto I liked. It had a girlish lack of authority.

“Cheers. The glare is blinding.”

Up close, I studied her designer swimming costume. It had a plunging neckline and complicated cutouts on either side of her pencil-line waist. She was reed-thin, with arms that weighed more in fuzz than actual meat. I wondered if she was body dysmorphia‑ed--a dinghy who thought herself a barge.

I took off my dress without making my usual efforts to hold in my stomach. Mine weren’t abdominals, they were abominables.

“Summer always makes me nostalgic for the twenties,” I said.

“You couldn’t pay me to be twenty again.” She began to frown, then glossed it over with the poor impression of a smile.

“I meant the 1920s. I would have worn those required leg coverings quite happily.”

She began to protest--“Oh please”--but lost conviction.

I slapped an invisible mosquito. “So many mozzies.” Accent as understated as a football chant.

She smiled and named a brand of natural repellent made from clove and catnip.

“Back in Britain, natural insecticides include a gin and tonic before dinner.”

“Right. You’re English.” A look of micro-rage flickered over her face. “I should have picked up on your accent. Haa-aah. I must be dazed from my massage.”

Her daughter scurried over, dripping water and pleading: “Now can we have ice cream?”

“We’ll order lunch first. OK?” She shrugged as if discounting herself.

Privately, I wondered whether it was more difficult to say no to an adopted child. Her girl was Chinese. She looked Jewish or Italian.

“How did you manage a massage with that adorable little one?” I asked.

“It’s a weekly tradition. I come up from Woodstock with my girlfriend Abigail--”

“Oh, you know Abigail Brown?”

“No, Abigail Wheeler. Do you know her?”

I shook my head. I didn’t know a soul in Woodstock. I just wanted to suggest we traveled in the same circles.

“Abigail and I buy season passes every year. She watches the girls by the pool while I have a massage or a facial. Then I return the favor and watch her little girl, Chloe. It keeps us sane.”

“She’s at the spa now?”

“She was earlier. She had to leave early today.”

“What a brilliant system. I think the last massage I had was prenatal.” I gestured toward the kiddie pool, where Fitz was half-submerged and Kitty, holding the metal railing, was making kicking splashes. “She’s mine. Kitty. She’s two. And Fitz, over there, is five.”

“Those are names you don’t hear often.”

“Kitty’s short for Katherine.”

“Kitty. That’s cute.” She made an awkward purring sound, then reached for her dinging phone.

“I’m Gracie. Mueller. By the way.”

But I had electronic competition. She was preoccupied with something: an app, or a text or a gif of a cat playing snooker.

Excerpted from The Drama Teacher by Koren Zailckas. Copyright © 2018 by Koren Zailckas. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Buy on Amazon | Barnes and Noble

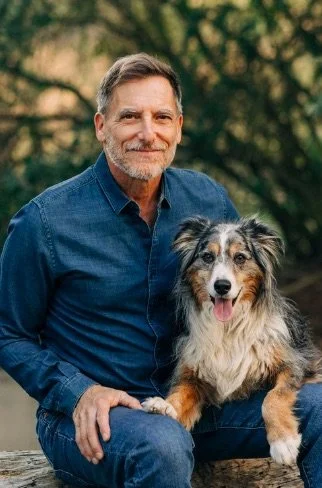

About the Author

Koren Zailckas is the author of the internationally bestselling memoir Smashed: Story of a Drunken Girlhood and has contributed writing to The Guardian, US News & World Report, Glamour, Jane, and Seventeen. She currently lives with her family in the Catskill Mountains of New York. To learn more, visit korenzailckas.com.