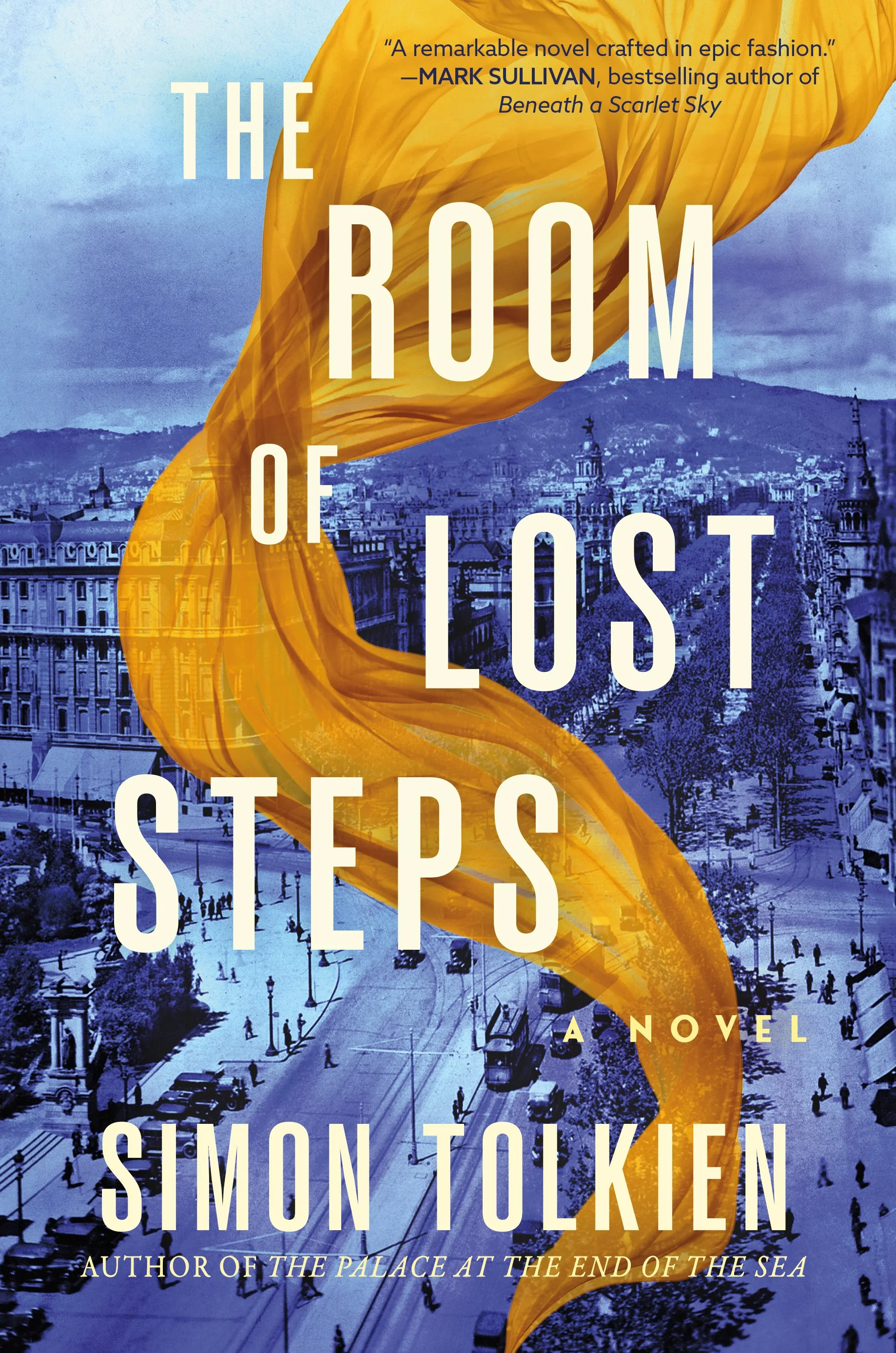

You are the grandson of J.R.R. Tolkien. How did that affect your writing career?

It’s hard to analyze one’s own character and development, but I think that two vital clues in my case are that I was born the grandson of one of the most famous and well-loved writers of the 20th century and that I never wrote a word of fiction until I was forty-one, even though I clearly had the capacity to do so. I have no doubt in my mind that the two are linked.

I was not a confident person in the first half of my life. I was unsure of my identity and self-conscious in the way I expressed myself, and this fed into an undermining sense of being overshadowed by my grandfather and his immense achievements. But like a pressure cooker inside, my desire to write ultimately forced itself to the surface in the years following the Millenium. I cut back on my work as a criminal law barrister and began my first novel, and when it was turned down, I simply wrote another. Suddenly I was determined when before I had hidden away. I developed my talent, learning as I went, progressing from plot-driven crime thrillers to historical fiction in which the characters became as real to me as actual friends.

My sense of being overshadowed by my grandfather’s achievements had fortunately never poisoned me against The Lord of the Rings. I have always loved Middle-earth and I read the books aloud to both my children. As a novelist, I have never been tempted to write fantasy, but I was attracted by the realism of my grandfather’s writing and the vitality of his storytelling. Whether hobbit or human, his characters are flawed, facing hard choices with extraordinary reserves of courage, and these were qualities I looked for in my own creations.

My grandfather died when I was fourteen, and with No Man’s Land, I feel that I reached the end of my journey to find him again and relate to him in a positive way. After fifteen years as a novelist, I had sufficient confidence in my writing ability to try to bring to life the experience of the British soldiers like my grandfather, who fought on the Western Front in the First World War, and to begin to understand the effect that that experience had on his imagination. As I wrote in the dedication, I felt that my book honored his memory, and I thought that he would have been proud of me. At last, my grandfather and his achievements had become an inspiration and not a block to my self-expression. I felt I was standing beside him and not behind him as I turned my thoughts to my next writing chapter: New York in the Great Depression and the Spanish Civil War.

How did you approach the research process for the duology - The Palace at the End of the Sea and The Room of Lost Steps?

My first three books were in the crime genre and plotting and writing took much more time than research. But the reverse has become true since I switched to historical fiction, and research for the duology ended up taking more than three years!

I knew that I was taking on a serious challenge with the Spanish Civil War. Spanish politics in the 1930s were fiendishly complicated and this has meant that there is a huge amount of historical study of the period but almost no novels. I read these studies because I knew I needed to understand the full picture if I was going to be able to simplify it and make it accessible to my readers, and I care deeply that the history in my books is accurate.

I realized that I was going to have to strike a fine balance between painting the relevant historical background but without ever allowing the novels to become a history lesson, because the provision of information for its own sake takes the reader out of the fictional world I am trying to create and make real. It helped that I was writing a coming-of-age story in which the reader could join my hero in his journey towards understanding Spain.

I knew that what mattered most, however, was bringing the relevant history to life, and so I read all the memoirs I could get my hands on, including the accounts written by the survivors of the Lincoln Battalion, searching for vivid passages that would inspire me. It was one thing to know that 2% of the population owned half the land of Spain in 1936; it was quite another to see the “bent-over men coming down the paths from the hills with tied-up bundles of firewood and pine cones on their backs”, looking like “some strange species of tree creature … not human at all.”

And the books’ scope and ambition grew organically as I worked, increasing the amount and diversity of information that I needed. It began as a novel about a War and ended eight years later as a portrait of an era with settings in New York, England and Spain.

Why is your novel called The Palace at the End of the Sea?

The palace at the end of the sea is Ellis Island, the famous immigrant inspection and processing station in New York Harbor. Early in the novel, the hero’s father describes to his son how he and his parents arrived there from Poland at the end of the 19th century, and how fearful they felt about whether they would be allowed into America. He tells him that on the ferry afterward, he “looked up at the towers of Manhattan and the stars blinking,” and it was the happiest moment of his life.

The boy, Theo, sees the red-brick immigration building and its towers from the boat when he leaves New York at the end of Part One, and recalls his father’s words, causing him to reflect on how his father followed his dreams and earned his fortune, only to lose everything in the Great Depression.

Theo can see through his father’s eyes that Ellis Island must have seemed like a palace after the long hard voyage across the Atlantic, but its shine seems tarnished to him now by the hardship and misfortune that he and his family have experienced in the Depression, and the partly ironic title reflects the most important theme of the duology – the relationship between hope and loss, illusion and disillusion, while also focusing the reader on the city of New York where Theo grows up and begins his journey.

Why does The Palace at the End of the Sea begin in New York? What did you learn about the city in the 30s from writing your novel?

All my books before the duology were written from a British perspective, and after finishing No Man’s Land, I wanted to take on the challenge of making my next hero an American. I soon realized that nationality wasn’t enough; I was going to need to show him growing up in America and his character being formed by that experience. I fixed on New York as the setting. It was an easy decision to make because I had always been fascinated by the city, exploring its streets and avenues until I was footsore on many previous visits. And the choice also made sense because I knew that my hero was going to fight with the Lincoln Battalion in the Spanish Civil War, and New York was where so many of the volunteers came from.

I began to research the city in the Thirties and was soon enthralled by the vivid variety of life that I encountered. I read about the Jewish immigrants who were worked to the bone in the garment sweatshops on the Lower East Side, and I was moved by the suffering of the unemployed in the Great Depression, queuing at the soup kitchens in the Bowery while the glittering skyscrapers multiplied in number above their heads, indifferent to their plight. Rich and poor, capitalist and communist, men and women of every color and creed, all caught up together in the melting pot of the great city.

I listened to the jazz music and watched the movies that New Yorkers listened to ninety years ago, and I tried to picture the speakeasies and the bath houses, and imagine the gaudy savage joy that they felt when they escaped for a day to Coney Island or watched Babe Ruth set Yankee Stadium alight.

All these strands came together in my mind to form the story of my hero’s father who rose from rags to riches, living the American dream, only to watch all that he had built fall to pieces in the Depression. The experience of this calamity and its terrible results mold his son’s character, setting him on the paths that will ultimately lead him to the war in Spain.

What is your hero, Theo Sterling’s greatest quality?

Courage. An alternative title for The Palace at the End of the Sea was The Anatomy of Courage. Theo cannot and will not back away from a challenge, even when he knows it’s going to get him into trouble. He wants to run, not walk. He makes a life for himself and his mother in New York in the most adverse circumstances but then runs after his future stepfather even though he knows that it will likely mean that he will have to give that life up. He jeopardizes everything that he has achieved at school in England when he joins his friend, Esmond, in a violent anti-Fascist demonstration in London, and risks torture and imprisonment when he participates in an attempted anarchist outrage in the village in Spain to which he has moved with his mother and stepfather. He constantly gets ahead of himself and lets his heart rule his head and then has to pay the consequences. But nothing can shake his belief that he can change the world, and he is forever inspired by a restless imagination, a capacity for intense friendship, and an instinctive response to beauty. He falls in love with the firebrand anarchist girl, Maria, through the prism of the love he already feels for rural Spain and continues to believe in the face of all the odds that in the end they can be together.

Why did you set part two of The Palace at the End of the Sea in a British Catholic boarding school?

The duology is a coming-of-age story and so I knew that my hero, Theo would have to go to school, and early on in the planning stage, I decided that it should be a Catholic boarding school called Saint Gregory’s located in rural England.

Later, I became nervous about this because I myself went to a similar school, Downside, in the 1970s and did not do well there, and I was anxious about whether this experience would lead me to become unconsciously satirical, turning the fictional school into a vehicle for exorcizing or rewriting my own history, and so losing sight of Theo’s development as a person in an utterly foreign environment that had nothing in common with all that he had known before in America.

But perhaps awareness of the pitfalls kept me on the straight and narrow, and I am pleased with the end result. Like me at the time, Theo is in search of an identity, but unlike me, he ultimately makes a success of his schooldays, while having formative experiences there that inform his later decisions in life. Thus,

his struggle against the school bully provides the foundation for his visceral hatred of Fascism, and the charismatic hold that his communist friend, Esmond, exerts over him, plants the seed of his belief that he can change the world.

And contrary to what I expected, Theo’s experience of Catholicism at the school turns out to be largely positive, and the humane influence of his housemaster, Father Laurence, is an antidote not only to Esmond’s extremism but also to the unquestioning emotion of his mother’s religion that Theo is repelled by, especially after the family move to Spain.

I enjoyed writing about school, and so perhaps good fiction is indeed good therapy!

Why is part 3 of The Palace at the End of the Sea set in Spain?

I knew from the outset that the book would be a coming-of-age story in which Theo, its American hero, would join the Lincoln Battalion to try and stop the Spanish Fascists from destroying the Republican government that had been democratically elected to reverse centuries of social and economic injustice. But as I developed the plot, I came to realize that it was not going to be enough for Theo to volunteer to fight for an idea of justice in the same way that the vast majority of the Lincolns did; he also needed to have a personal visceral stake in the War that would make it impossible for him to stay home. This meant that he would first have to live in Spain before the War and fall in love with the country.

So, I went to the primary sources and read all I could about what rural Spain was like in the mid-1930s: a world unchanged since mediaeval times that has since vanished almost without trace. I found out how the people lived and dressed and ate, and I tried to understand the centuries-old customs and beliefs that governed their lives. Street by street, square by square, I built an Andalusian village and called it Los Olivos, and in the end, I could see it and smell it and hear it, just like Theo, and experience the terrible injustice that lay beneath its beautiful surface, destroying it like a canker from within.

The Palace at the End of the Sea begins with the hero, Theo, meeting his Jewish grandparents for the first time. Why did you include a Jewish dimension in the story?

I have always been fascinated by Jewish culture, and the history of the Holocaust has haunted me ever since I first heard about it when I was a boy. Later, as a writer of historical fiction set in the first half of the 20th century, I have been interested in including the Jewish experience in my stories.

The key to my novel, The King of Diamonds, turns on the true identity of a diamond dealer who may have helped Jews to find safe passage out of occupied Belgium, or may instead have betrayed them to the Nazis, in order to steal the jewels that they hid in their clothing when they escaped. This storyline enabled me to explore the fate of the twenty-five thousand Jews who were deported to Auschwitz from the transit camp at Mechelen near Antwerp between 1942 and 1944.

In The Palace at the End of the Sea, I have written about the Jewish immigrants to New York in the early 20th century, who worked in the garment sweatshops of the Lower East Side. The hero’s father has left this world behind and renounced his Jewish identity by marrying a Catholic, but in the first chapter of the book, his son, Theo, meets his grandparents for the first time and finds out that he has a Jewish family history of which he had been completely ignorant up to then. Theo’s father tells his son that he must forget all that he has seen and heard, but instead Theo hoards his memories like treasure, and years later, one of his principal reasons for volunteering to fight in the Spanish Civil War is the need he feels to stand up against Hitler’s persecution of the Jews. In Spain, Theo is finally able to connect with his Jewish heritage and make that a real part of his identity.

Why does the Catholic religion play such a significant role in The Palace at the End of the Sea?

The Catholic religion plays a pivotal role in the book, because it is at the root of the broken relationship between Theo and his mother, Elena. Her faith is emotional, born of a childhood in Mexico which came to a sudden end when her parents were murdered by socialist government soldiers, forcing her to flee the country. But her son is a “child of New York City, where everything was man-made, and what you saw was what you got.” He doubts and questions everything, and feels smothered by his mother’s heartfelt certainties.

The tension between them escalates when they move to a village in Andalusia in Part 3. Elena believes that she has at last returned to her spiritual home, but the Spanish Church has little in common with its persecuted Mexican counterpart. It is immensely rich and identifies with the ruling class – the great landowners and the army. The poor feel that it has betrayed them and have turned to the anarchists who preach that religion is a lie used to deceive them and keep them in submission and ignorance. Freedom will only come “when the last marquis has been strangled with the guts of the last priest.” As the tension between the haves and the have-nots escalates, Theo and his mother move further apart and their love for each other cannot bridge the rift that has opened up between them.

Who was your favorite character to write in The Palace at the End of the Sea?

This is a hard question. Theo is the (flawed) hero of the novel, but I found Esmond de Lisle the most interesting character to create, partly because he is contradictory and elusive, so that like Theo, I could never be sure of what he was really thinking. Theo meets Esmond at school in England and quickly falls under his charismatic spell. Esmond has the best sense of humor of all the characters in the duology, and he has a genuine affection for Theo, but Theo detects a coldness in him. Esmond is his own person and doesn’t care what others think of him, but he can’t feel what others feel. His faith in communism is as strong as Theo’s mother’s is in God, but he expresses it cerebrally instead of emotionally like her.

I named Esmond after Esmond Romilly, who was Winston Churchill’s nephew and lived an extraordinary life until his tragic early death at the age of twenty-three. Romilly attended an English boarding school where he rebelled, publishing a left-wing magazine that achieved a national circulation. At eighteen, he joined the International Brigades and fought in the successful defense of Madrid against the Fascists, and then wrote a book, Boadilla vividly describing his experiences. Back in England, he fell in love with Jessica Mitford, who was one of the famous Mitford sisters. They eloped and spent a year travelling around America before he joined the Royal Canadian Air Force as a navigator. His airplane was shot down over the North Sea in 1941 and his body was never recovered.

Esmond Romilly’s life was an inspiration for some of the events in the duology, and his charisma was a quality that I have tried to convey in my portrait of Esmond de Lisle, but they are otherwise very different characters, not least because Esmond Romilly was never prepared to fully embrace communism, which makes him more akin to Theo than his fictional namesake.

Thee are not many novels about The Spanish Civil War but it’s a topic you took on. Why did you want to write about it?

The kernel of the idea came to me a long time ago when I read an article about the Abraham Lincoln Brigade – Americans who volunteered in the last years of the 1930s to fight for the democratically elected Spanish Republic, that was under attack from the Spanish army supported by Hitler and Mussolini. Thousands of them from many different walks of life – university graduates and mill hands, teachers and truck drivers, even a governor’s son – crossed the sea without any previous experience of soldiering and risked their lives to fight for their ideals; many never came back. I was astonished by their courage and sacrifice, and I thought that their story would make a wonderful subject for a novel. But I had other projects to fulfill at the tim,e and so I filed the Lincolns away in the lumber room of my memory.

Years later, I finished my novel, No Man’s Land that takes place between 1910 and 1919, and cast around for what I should write about next. My previous book, Orders from Berlin, had been set during the London Blitz of 1940, and I therefore looked to see if I could find an interesting subject that lay between the two world wars. It didn’t take me long to light on the Spanish Civil War. I remembered the Lincolns and thought that they could be a fascinating way into the subject, tying in with my wish to try and write for the first time from an American perspective, having emigrated to the States eight years before.

Full of enthusiasm, I began to read Hugh Thomas’s magisterial history of the Spanish Civil War, and one third of the way in, I felt my head spinning as I tried to make sense of the extreme complexity of 1930s Spanish politics. Drowning in a sea of acronyms, I began to understand why novelists since Hemingway had steered clear of the war. I thought of giving up but then dismissed the idea. The inaccessibility of the subject matter actually attracted me. I knew that beneath the surface there was a vital world waiting for me, peopled by men and women who had sacrificed everything to try and change it for the better, and as I pushed forward, I became determined that their stories should not be forgotten. It took me more than eight years to complete the journey, but I am happier than I can say that I stayed the course.

What is your writing process? What different stages did the duology go through in it’s development?

I try to be methodical. I chose my subject - the Spanish Civil War – and read the standard histories of the period and then began mapping out the barebones of a plot in my mind. This took many months and was, I think, the hardest part of the process, because I worried, as I have with previous books, that I wouldn’t be able to come up with something that I believed could work. Being an author is a lonely business and the awareness that the book doesn’t exist until you invent it can be very daunting. I spent many days on the sofa, gazing sightlessly into the middle distance, going up blind alleys. Patience is key and eventually, many months later, I felt ready to assemble what I had in a synopsis and send it to my publisher for discussion and approval.

With the synopsis agreed, I began the research process which involved travelling to relevant locations and reading historical studies and memoirs so as to build up a comprehensive database of relevant information on my computer. Amazon was an amazing resource because it enabled me to buy out-of-print books, so that I now possess an almost complete library of the Lincoln volunteers’ accounts of their experiences in the Civil War. It was hard to know when to stop the research and start writing because there was always more information available - another treasure trove waiting just around the corner!

I wrote the books sequentially from beginning to end, expanding out the planning documents and chronologies as the scope of the story grew. The end seemed very far away in the first year, and I had to force myself to think of the writing journey as segmented, with each of the six parts of the duology an end in itself. I imagined myself as a mountaineer climbing between base camps, keeping his eyes averted from the distant summit.

But I did finally reach the end and opened a bottle of champagne, before beginning the long process of revision and editing, which brought its own challenges. I was very lucky to have the help of two wonderful developmental editors, Beena Kamlani and then David Downing, but I had to discipline myself to listen to them and evaluate all their suggestions on their merits, overcoming the protectiveness I felt for my creation. Book as child!

And then one day, eight years after I began, everything was finished and I received the beautiful advance reader copies from my publishers, held them in my hands, and felt an intense sense of fulfilment and gratitude. For better or worse, I had created the books from nothing. They were the best I could do; they had become a vital part of who I am.

What do you enjoy most about writing?

I have never been any good with my hands, and for many years, I felt frustrated that I had no outlet for my creativity, so it makes me very happy now that I can create multi-faceted characters who exist independently of me. I believe in them and can share their hopes and fears, their successes and their failures.

Over time, my novels have increased in scope and ambition, and the duology is a portrait of an era set in three countries over a nine-year period. They require detailed research and preparation, and I enjoy using the skills I learned as a historian and a lawyer to assemble my diverse material and develop it into an organic whole.

Sometimes, when I am writing, I arrive at a point where the narrative seamlessly connects with something else in the story that I hadn’t seen before. At such times, I feel that an unseen hand is at work, guiding me. Writing becomes alchemy, at least for a moment.

What about historical fiction as a genre appeals to you as a writer?

As a child, I loved history. My mother had inherited a huge leather-bound book, Haydn’s Dictionary of Dates, and I would pass days reading the entries and building pictures in my mind of who the Moghuls were and what it would have been like to have lived in the Khanate of the Golden Horde. I could see Ivan the Terrible when I closed my eyes or at least my version of him and imagine Vasco da Gama’s terrified sailors rounding the Cape of Good Hope as the waves battered their ship. The past was another country, as alive as mine, and infinitely more wonderful than the sleepy English village where I grew up.

At school, history was my best subject, and I went on to study it at university. But I was always frustrated by the way it concentrated on the causes and results of events, avoiding the visceral reality of what had actually happened in the heat of revolution or battle. I preferred the great 19th century novels that made history real – the Brontë sisters and Dickens, Dumas and Tolstoy.

Twenty years later, I gave up being a barrister to become a novelist. I began with what I knew, writing courtroom dramas, but over time I became confident enough to leave crime behind and write character driven stories set in the first half of the 20th century. Finally, I felt that I had found my calling, bringing the past to life, so that I could recapture that sense of wonder I had as a child and convey it to my readers.

What are some recurring themes in your fiction writing?

In my first novel, Final Witness, the teenage hero believes that his father has married a woman who conspired to murder his mother; in The Inheritance, a young man, Stephen Cade is on trial for the murder of his father, and faces execution by hanging; in No Man’s Land, Adam Raine loses his parents in traumatic circumstances and must search for an identity in a hostile and alien environment. And in my two new novels, Theo Sterling suffers devastating losses and disillusionment while trying to find meaning and fulfilment in a broken world.

I think this focus on the struggles of young men without siblings in their teenage years is no accident. I consider myself now to be a determined person who works hard to accomplish clear-set goals - I couldn’t have written the novels I have over the last twenty-five years without a strong sense of discipline and purpose. But, as an only child of divorced parents and later as a teenager, I was very different. I lacked confidence and was often unsuccessful in my endeavors, and I think that my fiction writing has been a way for me to connect back to my younger experience and explore where a search for identity can take a person who is deeply unsure of themselves.

My interest in the vulnerability of the young has also led me to write about the effects of trauma on their psychology. My heroes suffer from family estrangement and sudden loss of friends and parents, and in my more recent novels, they fight in terrible conditions on the battlefields of the Western Front and the Spanish Civil War. Throughout, I have been interested in exploring the positive and negative effects of these experiences on the minds and souls of those who are still in a formative stage of their development.