Meet the Women Who Knock Alpha Heroes Off Their Feet: Alpha Heroines by Delaney Diamond

/The alpha hero has had a good run in romance over the years, and for the most part, readers adore men who are confident, powerful, and in control.

But today, I want to talk to you about the alpha heroine. She’s the kind of woman who possesses the same intensity and strength and can knock even the most alpha hero off his feet.

In my novel, Thiago (Family Ties, book 6), India Monroe embodies that kind of heroine. She’s intelligent, resilient, and refuses to be a pushover—not even for Thiago Santana, her wealthy, commanding boss with whom she is having an affair.

Alpha heroines are as tough as the hero

Alpha heroines don’t bow to power. They challenge the hero in a way few people in his life would dare. For example, Thiago is used to striking fear in the hearts of his staff. When they see him coming, they scramble out of the way, and when he asks them to complete a task, the only answer he expects is “yes.”

India is not so easily intimidated. As an alpha heroine, she doesn’t back down from his dominance, making each clash a conflict of equals. That makes their chemistry explosive. She’s not afraid to push back, and secretly, he loves it because he’s finally met his match.

India’s jaw tightened. “We’re marketers, not magicians. I brought you a strategic rollout after you asked for a proposal less than two weeks after the scandal hit the news. You want quick results, then expect half the quality. Unless you want me and my team to pull all-nighters every night.”

His eyes flicked over her, the way she stood with one hand on her hip, her full lips pressed together in anger, challenging him with her voice and a deadly stare. She was acting as if she was the one in charge, looking at him as if she were ten feet tall.

So damn sexy. He fought the smile threatening to pull the corners of his mouth upward.

“Careful,” he said, his tone low and dangerous, hiding his amusement.

He watched as she moved closer. “You don’t scare me, Thiago.”

Alpha heroines know their worth

Just like the alpha hero, the alpha heroine knows she’s a catch, and India is no different. She’s smart, educated, and does a great job as the vice president of marketing for Santana International’s U.S. operations. After a health scare, she realizes that she’s selling herself short in her no-strings relationship with her boss and starts dating other men. She wants more. She deserves more.

Thiago, however, is not happy when he finds out that she’s seeing other people.

“Is the good doctor the only other man you’re seeing?” Thiago asked in an overly pleasant voice.

India averted her eyes.

Thiago let loose a stream of Spanish curses. “How many others are there?” he demanded.

“You make dating sound awful, and it’s not. Kiara set me up with a friend of her husband’s, and we went out last night. Why do you care?”

“How could you ask such a question!” Thiago bellowed.

Can you tell he was livid? I’m surprised he didn’t pop an artery. Because India has started exploring her options, Thiago has to scramble to hold onto the only woman who has ever made him reconsider the single life.

Alpha heroines redefine the power dynamics of love

Traditionally in a romance, the alpha hero calls the shots. He pursues or protects. But alpha heroines meet these powerful men with a wall of calm defiance and bend the norms.

In the case of India and Thiago, when Thiago finds out that India is seeing someone, he declares that she belongs to him and demands that she stop seeing the other man. She’s an alpha female, so of course, they butt heads.

“I am not the property of any man—”

“Spare me the feminist bullsh*t. I’m not sharing you, and that’s final.”

Her lips pressed together. “All right, Thiago, you want me to stop seeing him. Fine. But I’m confused because you and I don’t have that kind of relationship. We sleep together, but we barely know each other…”

“What do you want to know? Ask me anything,” Thiago said.

“Really?”

“Yes. Really.”

“Okay.” She carefully placed her phone and the coffee on a side table. “Why are you so mean?”

That wasn’t exactly the kind of question Thiago had in mind, but India used this conversation to call him out on his hypocrisy and point out his flaws. We would expect nothing less from an alpha heroine.

Alpha heroines force the hero to evolve

These women have the power to change the hero by standing firm and forcing him to conduct a self-evaluation. As the CEO of Santana International and coming from a wealthy family, Thiago thrives as a man in control of his environment and the people in it.

But during the course of the story, you’ll see him evolve. He becomes more compassionate, a prime example being when he learns of India’s lupus and implements a company wellness program that benefits all the employees—because of his love for her.

Alpha heroines expect respect, honesty, and equality in their relationships and don’t just tame the hero—they transform him.

Conclusion

Writing Thiago allowed me to explore what happens when two strong personalities come together, their fiery traits creating conflict in the boardroom as well as the bedroom. If you enjoy reading about fierce women who challenge powerful men and knock them off their feet, India and Thiago’s journey might be your next favorite read.

About Thiago:

A no-strings workplace affair spirals into a tug-of-war of emotions.

Thiago Santana didn’t claw his way to the top of Santana International to get sidetracked by love. As CEO, he’s driven and focused, taking his only break on Friday nights when he indulges in the one temptation he can’t resist: his VP of marketing. But when she starts canceling their meetings, it throws his carefully constructed life into chaos.

India Monroe has always played by her own rules. Sharp, independent, and very ambitious, she has never needed anything beyond her no-strings arrangement with Thiago. But a health scare jolts her into wanting more—more time, more emotion, more commitment.

Now their relationship has changed. Every touch carries tension. Every glance holds a question. If neither surrenders, they might lose the one thing they never meant to risk at all: each other.

Excerpt

After the door closed behind them, tense silence reigned between Thiago and India.

One hand on her hip, she fixed her dark eyes on him.

“Do you have something to say to me?” Thiago asked, taking a seat on the edge of the table and folding his arms.

“You undermined me in front of my team.”

“You brought me an unacceptable strategy.”

Her jaw tightened. “We’re marketers, not magicians. I brought you a strategic rollout after you asked for a proposal less than two weeks after the scandal hit the news. You want quick results, then expect half the quality. Unless you want me and my team to pull all-nighters every night.”

His eyes flicked over her, the way she stood with one hand on her hip, her full lips pressed together in anger, challenging him with her voice and a deadly stare. She was acting as if she was the one in charge, looking at him as if she were ten feet tall.

So damn sexy. He fought the smile threatening to pull the corners of his mouth upward.

“Careful,” he said, his tone low and dangerous, hiding his amusement.

He watched as she moved closer. “You don’t scare me, Thiago.”

“Hmm. That’s a problem, don’t you think?”

She held his gaze, her chest rising and falling with shallow breaths. Electricity crashed between them—anger laced with sexual awareness. He ached to reach for her but resisted the urge. They didn’t cross the line at work. Too risky.

“Was there a reason you asked me to stay behind?”

“I wanted to make sure you can meet my… demands.”

She flicked her tongue to the top left corner of her mouth, toying with him. “Don’t I always?”

Thiago clenched his hand into a fist on the table. Damn, this woman. Insatiable desire for her consumed him with no end in sight.

India turned on her heel. “If I’m going to meet your deadline, I have to go.”

She was halfway to the door when his voice stopped her.

“India.”

She stopped but didn’t look back.

Thiago pushed off the table and took a few steps in her direction. “Are we still on for tonight?”

She turned her head slowly, eyes narrowing into an expression hot enough to curdle milk. “Maybe,” she said coolly.

Thiago exhaled through his nose, the corners of his mouth twitching upward. Then she walked out without waiting for a response. She was infuriating, but she was the best part of his week.

Knowing her, she’d remain pissed right up until he saw her later.

Which meant the sex tonight would be incredible.

Buy on Amazon Kindle | Paperback | Bookshop.org

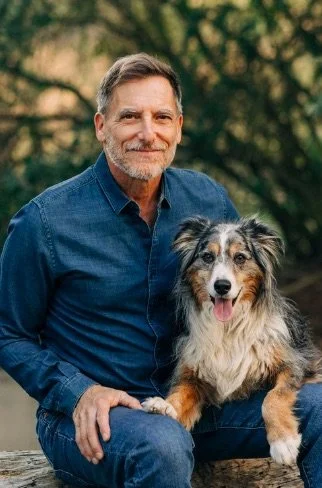

About Delaney Diamond

Delaney Diamond is the USA Today Bestselling Author of more than 60 contemporary romance and romantic suspense novels, and dozens of romance short stories. She reads romance novels, mysteries, thrillers, and a fair amount of nonfiction. When she’s not busy reading or writing, she’s in the kitchen trying out new recipes, dining at one of her favorite restaurants, or traveling to an interesting locale. To get sneak peeks, notices of sale prices, and find out about new releases, join her mailing list. And enjoy free stories on her website at delaneydiamond.com.

Giveaway

Which alpha heroine trait do you most like to see in a romance novel? Tell me in the comments for a chance to win an eBook copy of the first two books in the Family Ties series, Audra – The Prequel and Ethan.

One winner will be randomly selected and announced in the comments.

Eligibility: Open to international entrants.

Deadline to enter: November 15, 2025.