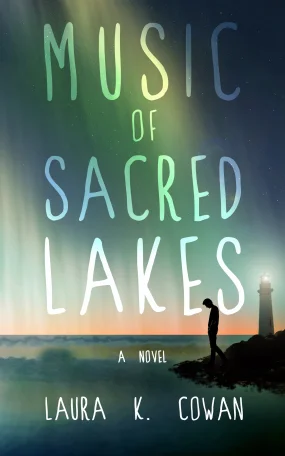

Read an excerpt from Music of Sacred Lakes by Laura Cowan

/About the Book

Peter Sanskevicz doesn’t belong anywhere. He doesn’t want the sixth-generation family farm his great great-grandfather unwittingly stole from its Odawa owners, and can’t continue his jobs serving “fudgies,” tourists in Northern Michigan who seem more at home than he is. He can’t seem to take charge of things or do anything but make a mess. Then, Peter accidentally kills a girl.

Seeing his life is at risk, his friend takes him to his uncle, a pipe carrier of the Odawa tribe, who tells him he must live by the shores of Lake Michigan until the lake speaks to him. Peter lives and loves and rages by the shores of the great lake, haunted by its rich beauty, by strange images and sounds that begin to pursue him through his waking and sleeping hours, and by the spirit of the dead girl, who seems to be trying to help him. One day, he finally finds an inner silence. And then, he hears what the lake has to say to him. A story about reconnecting with the source of your life and your joy, Music of Sacred Lakes gives voice to the spirit of the land and lakes that gave birth to us all.

With this second and astonishingly sophisticated novel, Dreaming Novelist Laura K. Cowan cements her reputation as one of the most imaginative new American Fabulists, a writer of spiritually-oriented magical realism, literary fantasy, and visionary fiction in the line of Alice Hoffman, Ursula K. Le Guin, or Paulo Coelho, but characterized by an electric mix of lyrical language, an evocative sense of place, and quick-moving narrative that harkens back to a time when literary fiction was served up raw and ghost stories weren’t told for their sad and scary parts.

Excerpt

Chapter One

The Accident

The whole world used to be this quiet. Here in the land of the inland seas, land of tamarack swamps and aspen forests, of sand dunes watched over by ancient stands of virgin timber and dense second-growth forests, the quiet remained. This land, in Northern Michigan, ever so slightly closer to the North Pole than the Equator, was a paradise of endless days in the brief and blinding summers, a haven for the thinker and the sleeper over the long snowy winters, and a welcoming place for an unhappy life.

It was here, in East Jordan, on the bottom of Lake Charlevoix, which emptied into mighty Lake Michigan with its magnificent gold and wine sunsets over sand-scented waves—it was here, on the bottom of the economic food chain—that Peter Sanskevicz was born.

It wasn’t that Peter didn’t belong. On the contrary, his family had belonged to East Jordan’s history for six generations, part of the first wave of white settlers to commandeer this paradise from the Odawa Indians who used it for summer hunting and fishing grounds before them. But Peter didn’t want to belong to this tradition of homesteading and lumber milling in the Great Silent North. He didn’t want much of anything he had, in fact, and that wasn’t much.

He had burned through too many jobs over the last year and a half since leaving his parents’ farm—still the same eighty acres homesteaded by his great great-grandfather beginning in 1865. When he couldn’t take haymaking and cow milking anymore, Peter had waited tables in Charlevoix by the Big Lake, worked as a janitor at the local cherry and vegetable canning plant in East Jordan, and finally piloted a boat for fishing tours on Lake Charlevoix. This last job was his favorite, as fishing with his friend Derek Negeshe had been one of Peter’s great loves in childhood. He still headed out to the Jordan River for fly fishing once in a while, but now much of his time was taken up between his two part-time jobs: driving a garbage truck and gardening for “fudgies,” tourists from Chicago or Detroit who came up here in the summers to buy the world-famous fudge and sail their yachts.

Peter hated his job, and he hated the fudgies, which wasn’t such an unusual sentiment up here. Why did they have to stare at him like some sort of living museum piece? It was amazing that they saw him at all, given as he was to working service jobs that tend to make people invisible—or at least anonymous.

It was to the local waste collection center north of the Little Traverse Bay that Peter was driving one day with Derek when his life, the one he so desperately despised, fell apart.

He had taken Route 31 from Charlevoix up to Petoskey, the scenic two-lane highway that ran along the coast of Lake Michigan and into the bay. The sun was shining out over Petoskey, built like an amphitheater on the hills above the rocky south shore. The waves were calm, typical for early June, and Peter had pulled the garbage truck off onto the gravel turnout and rolled down the window to smell the clean breeze off the lake. But even the wind couldn’t clear the stench of garbage from his nostrils. He could smell it on his skin—in his skin. It never scrubbed out anymore. He had escaped his parents’ farm for this?

Suits you, he heard his father’s voice in his mind.

The truck was ticking as it cooled, the only other sound the waves of Lake Michigan rolling into the bay before the two boys, who sat side by side in the front seat.

“Do you ever think about getting back out on that lake?” Peter asked.

Derek responded by looking across the bay, to his home in Harbor Springs. In these wave-hushed northern lands, people felt little need to fill the space with words. And Derek was quieter than most, silent until spoken to unless he had a good joke to share just like the rest of his family, who were descended from the Ojibwe and Odawa tribes native to these shores.

Derek finally returned to him. “Yeah,” he said.

Then he chuckled. “You remember when we took that bait from Mr. Pulowski’s docks and hauled in our own catch in my canoe?”

Peter laughed. “We could hardly fit the fish in your bucket,” he said, remembering them flopping around so hard they almost upset the boat.

“Those were good times,” he added. “The best.”

The call of seagulls filtered across the harbor.

“That lake used to mean something,” Peter said, turning to him. “What’s the point of anything if this is what we do it for?” He pulled at his jumpsuit. “How did we end up like this, man?”

Derek shook his head and looked out toward the open lake. The multi-million-dollar homes of the fudgies were just beyond his window on the right. Peter knew he didn’t want to see them.

“You’ve changed,” Derek said. “You remember when my parents were drinking in high school.”

“I’m glad things have gotten better for you,” Peter said.

“You hung out with me all those nights,” Derek reminded him. “You were my anchor. Now it’s like you’re drifting.”

The gentle waves were folding onto the birch-lined shore below Peter’s vision by the side of the road. Below the water, small-mouth bass, perch, and whitefish were just starting to grow and swim farther out above the boulders that lined the lake bottom. On the east end of the bay by the state park the bottom was sandier, much like the rest of the west coast of the state. Singing sand, they called it. It squeaked delightfully under your feet and sifted through your toes like sugar, warm and dry half an inch down even on a rainy day.

Peter sighed. “I know,” he finally said. “This place used to make me happy. But ever since I realized I couldn’t take my parents’ farm, I haven’t been able to find anything to replace it. Now nowhere feels like home.”

He turned to Derek, and saw him wiping a tear from his eye. Peter looked away to give him privacy.

“You were studying down at State,” Peter said. “What made you come back here and take this job?”

Derek shook his head, but he didn’t reply.

Peter sighed again. He took one last deep breath of fresh air, then turned the key in the ignition. The garbage truck roared back to life, and they pulled back onto the highway heading into Petoskey. The lake shimmered away from them on their left.

Maybe I will get back out on that lake again, Peter thought. If I can get the time off.

They passed the mansions of the fudgies on the lake side of the road, and the simple homes of the locals on the inland side. Soon they were surrounded by the outlying businesses of town and the old summer homes of Bay View. Here and there public parks opened to the shoreline, and Peter could see the sailboats out on the bay. His heart pulled in his chest. To be on those waves again, where everything had once made sense. No one owned the waves.

Gulls were soaring out over the water, and he imagined himself to be one of them, skimming over the breakers out on the blue horizon. He saw a flock of sandpipers skittering along on the wet shore by the harbor below. The sky was Michigan blue, all fluffy and filled with the white light of clouds passing over.

A stiff breeze off the lake flipped the leaves of the cottonwoods and shivered through the birches by the roadside. Peter inhaled the scent of clear water and fish and seaweed, and suddenly felt a pain deep in his stomach. How long had it been since he had gone out in Derek’s canoe for deep-water fishing? Derek had been down south at school for so long, he couldn’t even remember. Yes, he had to get back out on the lake. That smell, the sweet breeze on his fingers, the water flowing around the prow of the canoe.

They slowly passed through town, then accelerated as the road opened up past the fudge shop and turned north toward Harbor Springs. They passed the star-shaped store for Indian jewelry and the brick building that had recently become a brewery. It reminded Peter of East Jordan, this building. Five stories tall and narrow, obviously old, maybe an ancient factory or train depot from the days when they still thought the towns here would flourish.

“Peter!” Derek yelled.

Peter’s attention was jolted back onto the road. A flash of sunlight blinded him for a moment, but then he saw what he had done.

His muscles froze.

He had drifted into the oncoming lane of traffic. And what had been clear road just a moment before was suddenly filled with a red sedan. The driver was too shocked by the enormous truck to even honk his horn.

The car had just materialized around the bend, and now Peter was running out of road. He yanked the steering wheel to the right, not able to understand what Derek was shouting now. The garbage truck leaned to the left as it careened off the road toward a stand of jack pines between two strip malls.

Peter watched the little red car veer the same direction they were heading. It was too late to correct his course. The garbage truck and the red car ran parallel off the east embankment of the road, the truck on its two left wheels.

Then, the truck tipped.

It hovered over the red car for an eternal moment. Derek was grabbing at him, yelling. All Peter could see was the roof of the car below his window.

Then it rose to meet him.

There was a horrible crunch, the roof smashed up into Peter with a rush of broken glass.

He felt the impact as if he were underwater.

And then he was, a boat slowly sinking to the bottom of the lake. The light filtered out of his vision. And he was gone.