Spotlight: The Hot Summer of 1968 by Viliam Klimacek

/In the spring of 1968, the Czechoslovakian Communist Party introduced “socialism with a human face,” known as “Prague Spring.” Suddenly the citizens of Czechoslovakia enjoyed the freedom of the Press, an end to arbitrary wiretaps, and the right to travel without prior authorizations and visas. Their borders opened to the West, consumer goods appeared in the stores, and the winds of freedom blew over the country. That summer, Alexander and Anna boarded their Skoda Felicia, a brand-new convertible, to join their daughter Petra in Bratislava, where she had just completed her brilliant medical studies. Tereza, the daughter of a railway worker who survived the concentration camps and a Pravda editor who had long taken in Hungarian refugees, stayed in a kibbutz in Israel to reconnect with her Jewish culture. Józef, a pastor defrocked for refusing to denounce parishioners to the Party, delivered his first uncensored sermons on the radio.

But these reforms were not well received by the Soviet Union, and in late August of 1968, the USSR sent half a million Warsaw Pact troops and tanks to occupy Czechoslovakia and put an end to this brief experiment. Every citizen had to make a choice: leave or stay? Thousands of Slovaks fearing retribution fled their homeland—some escaped to Vienna—only an hour away by train, others fled farther afield to England, Israel, South America, Canada and the United States.

Celebrating the identity of a people, its folklore, its beauty, and its vitality, Klimacek vividly retells in THE HOT SUMMER OF 1968 the stories of ten real people (whose names have been changed) enmeshed in this difficult moment in history and reveals the impact of these rapidly moving events on his characters and the lives of their families. They all made the decision to leave their homeland and depart on the perilous journey seeking refuge and freedom in new countries. Some saw their families torn apart; others lost all their possessions or were dispossessed. And, like all immigrants, they had to rebuild their lives and livelihoods. What were their challenges? How successful or happy were they? Would they ever be able to return or reconnect with their families in their homeland? They all now became part of a growing Slovak diaspora in the modern world.

Excerpt

The Secret Police were again looking for Jozef in the Radio Building. He knew they were after him, but he also knew they had a lot of work. The list of people they were looking for was enormous, and every day some of those they could not find would be moved from the “Unable to Contact” column to the “Emigrated” column.

His superior greeted him, face pale. “Jozef, they just left. I haven’t told you anything and I haven’t seen you.” He shook his hand. “Good luck.” Jozef had just come back from recording the famous speech in which a politician talked about the border being a promenade. There was no need to wait any longer and no reason to keep up false hope. A failed pastor and actor, as the people responsible for arresting him called him, he had one last opportunity to leave Czechoslovakia, or he could put on a prison uniform and let his family be persecuted.

When he arrived home, Erika was whistling in the kitchen, a sign that she was in an excellent mood. She had just finished marinating the rabbit and had managed to get fabulous bacon at the market. Peter was watching with interest as she sliced it into tiny white cubes. Jozef stood for a moment in the hallway, summoning the courage for what he had to say. Then he entered.

“We have to leave.” “Leave? And go where?” “To Austria. They wanted to arrest me today.” “But I’m frying the crackling!” Erika spoke like a practical woman. They had to leave now, while she was frying the crackling and marinating the rabbit? Where would they go? Dinner was almost ready! Not for her, but for them! But she didn’t say what was going through her mind, knowing that her husband was right. They had to leave.

“Luckily, I have a full tank of gas. Pack warm clothes for the winter.” “That doesn’t sound temporary, does it?” “Austrian Radio will help us. They’re employing our people and will get us work and housing.” Peter followed their conversation attentively. “Mum, where are we going?” Erika started to say, “on a vacation,” but her voice broke. She embraced the boy, but he shouted joyfully. Vacation! He had to pack his little cars.

During his last trip to the Radio Building Jozef returned his reporter’s tape recorder. He wouldn’t let them make a thief out of him. He went to see their neighbor in the building, the one who had called them that August night and told them about the Soviet invasion. He left all his receipts with her, showing that he had paid off his television and the fridge. There was nothing left to say.

His biggest regret was that he couldn’t say goodbye to his mother. She told him that police from Modra were even looking for him in their vineyard. He was in a terrible predicament, having to leave without kissing the person who had sacrificed so much for him.

So, he called Erika’s sister. Anna answered after a long pause. Her voice had changed. It sounded tired, as if coming from a deep well. “Hello? Is that you, Anna?” “Jozef? Where are you calling from?” “From a phone booth. How are you?” “Well, you know. Petra left.” “I know… please don’t cry. Everything will be fine. I have very little time… I wanted to hear your voice.” “I’m happy you called.”

“I have a favor to ask of you. Could you visit my mother, now and again, when you’re in the area? She has no phone, as you know. Tell her I love her very much.” “I will, don’t worry.” “Say hello to Alex.” “I wish you the best of luck.” Jozef put down the receiver. The silence interrupted by electrical frequencies in the phone spoke more eloquently than dozens of words. He could be silent and yet he’d said everything.

Captain Poliačik, a quiet forty-year-old man, was in the Passport Office. He gave Jozef and his family permits to go to Austria without asking any questions. His department had been doing this all summerlong without stopping anyone. Anyone who wanted to leave could get out. Jozef thanked him and left the office.

That day Captain Poliačik gave out several other travel permits. At the end of the day, he wrote one for himself and his wife and children. Then he wrote a letter to his superior that would arrive by mail two days after he left the country. “As a Communist Party member, I should stay, but as the father of a family a family I cannot.”

Buy on Amazon

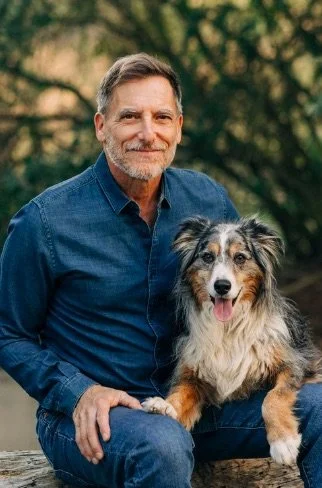

About the Author

Viliam Klimáček graduated from Bratislava University's Faculty of Medicine. Co-founding the alternative theatre GUnaGU in 1985, he has been its actor, director, and playwright. In the mid-1990s he gave up medical practice, devoting himself entirely to the theatre and writing. His most successful books include the novels Naďa má čas (Naďa is Not in a Hurry, 2002), Námestie kozmonautov (2007) and especially Bratislava 68 : Été brûlant (Horúce leto 68/The Hot Summer of 68, 2011).

ABOUT THE TRANSLATOR: Peter Petro, the translator, Emeritus Professor in the Department of Central, Eastern, and Northern European Studies at the University of British Columbia, was born in Slovakia, earned his B.A. (1970) and a M.A.(1972) in Russian literature at the University of British Columbia and his Ph.D. in comparative literature (1978) at the University of Alberta. He is the author of several books including a translation of the prize-winning novel by Milan Simecka, The Year of the Frog.