Q&A with Karen Warner Schueler, The Sudden Caregiver

/Where/When do you best like to write?

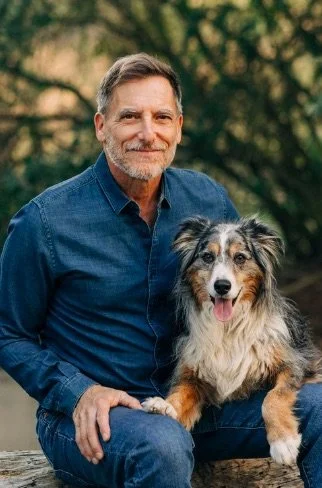

I’m an early riser. I like the morning quiet, a cup of coffee, an open laptop and a blank screen. For most of my life I wrote with pen and paper, typing up my stories later. Writing on my laptop is faster, easier, and I’ve gotten good at the brain-heart-fingertips connection. When I started writing The Sudden Caregiver, I was a new widow, raw with grief. It was spring in Beaufort, so I took Fenway, my coffee and laptop, mornings, out to my porch, where I could look up from my writing at any time and catch a dolphin breakfasting in the shallow water around my dock. When the weather is fine, that’s still my favorite place to write. When the weather isn’t fine, I write at my kitchen counter.

What do you think makes a good story?

I was educated by the Sisters of Saint Joseph, so, as a writer, the obvious answer is “man against man,” “man against nature,” and “man against himself.” Something must be overcome and the protagonist must be changed by it. I prefer Eudaimonic endings to apocalyptic ones. Eudaimonia is Aristotle’s ancient concept that, while the protagonist might not have a classically happy ending, they have evolved and grown into their best self. They are engaged in meaningful work, pursuing it with purpose.

In my book on caregiving, for example, you know in the first sentence that my husband has left us here on earth to make our way without him. By definition, this story does not have a traditional “happy ending.” But the point of the book is what I call “The Caregiver’s Paradox,” that caregiving sucks and is a source of meaning and well-being. My book, definitely “man against nature,” takes you on a journey of resilience-building in the face of illness. It does not end with Joel being cured. That would be a happy ending, but that’s not real life. It does end with the lessons I learned. That’s a Eudaimonic ending.

As a reader I also appreciate precise and significant emotional detail. John Updike was the master of this. He mentions his character seeing his married lover’s car in the parking lot of the grocery store – a mundane suburban detail, yet it conveys a kind of naïve happiness that has not yet confronted the reality of their situation. His work is filled with this kind of detail.

What inspired your story?

My own lived experience as a caregiver. I kept a daily journal from the time of my husband’s diagnosis well beyond the first year after his death. I was and am inspired to help other caregivers, everywhere. There are 45 million in the US alone. How can I hold a light up for them on the path that I just traveled?

How does a new story idea come to you? Is it an event that sparks the plot or a character speaking to you?

Buy on Amazon

When I became a caregiver, I was looking for a roadmap to inform the journey ahead and couldn’t find one that would help me corral the future into something manageable. My need to write, to create, is sparked by my wish to fill a void, to help others by sharing something I’ve become sure of.

Is there a message/theme in your book that you want readers to grasp?

That caregiving is both a source of stress and a source of well-being but you need to intentionally embrace that notion, not just hope it happens. If you do embrace it, it will happen. There’s research and evidence on that point. It’s not just luck.

What was your greatest challenge in writing this book?

In a word, grief. In order to help other caregivers benefit from my experience, I knew I would write this book even before Joel died. The week after his funeral, I joined a writing group run by one of my colleagues at Penn – now a good friend – Kathryn Britton. During the first year of widowhood, my grief and fear were so profound that they stunned me. They rolled over me in waves, like driving in and out of a thunderstorm. Pounding rain one minute, spangling sunshine the next.

Writing this book was my form of grieving, of processing all Joel and I had been through together and accepting the fact that Joel had left me to do this part of it alone. It is incredibly painful to write about the loss of your husband and life partner, who had defined every aspect of your life. Often writing about what happened brought the pain front and center. But then I’d write through the pain and find something beautiful and necessary on the other side of it. It took me four years to write this book, partly because it was so emotionally demanding.

Who are some of your favorite authors?

Winston Churchill. Ernest Hemingway. John Steinbeck. John Updike. Anita Brookner. Elizabeth Berg. Milan Kundera. Hilary Mantel. Eric Larson. Annie Lamont. Isabel Wilkerson. I’ve read more than one book – sometimes all their books -- by each of these authors, so I suppose I like authors who create a body of work that I know I will look forward to reading. I also read a fair amount of non-fiction that presents ideas I can leverage in my work. Martin Seligman. Adam Grant. Barbara Fredrickson. Angela Duckworth. Jonathan Haidt.

What’s the best writing advice you have ever received?

My late husband, Joel Kurtzman, published 20 business books across his lifetime. He was a journalist and an editor. Even though this is my first book, I’ve always been writing something – short stories, how-to marketing or leadership advice. Whenever I was stuck, he’d say to me, “Just write the first sentence.” This combines two of my favorite pieces of advice for writers: Ernest Hemingway’s, “All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know.” And Annie Lamott’s, “bird by bird,” referring to a time when her young brother was struggling with a homework project about birds. She says, “Then my father sat down beside him, put his arm around my brother’s shoulder and said, ‘Bird by bird, buddy. Just take it bird by bird.’”

What is the one book no writer should be without?

Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style. The Chicago Manual of Style is a close second.