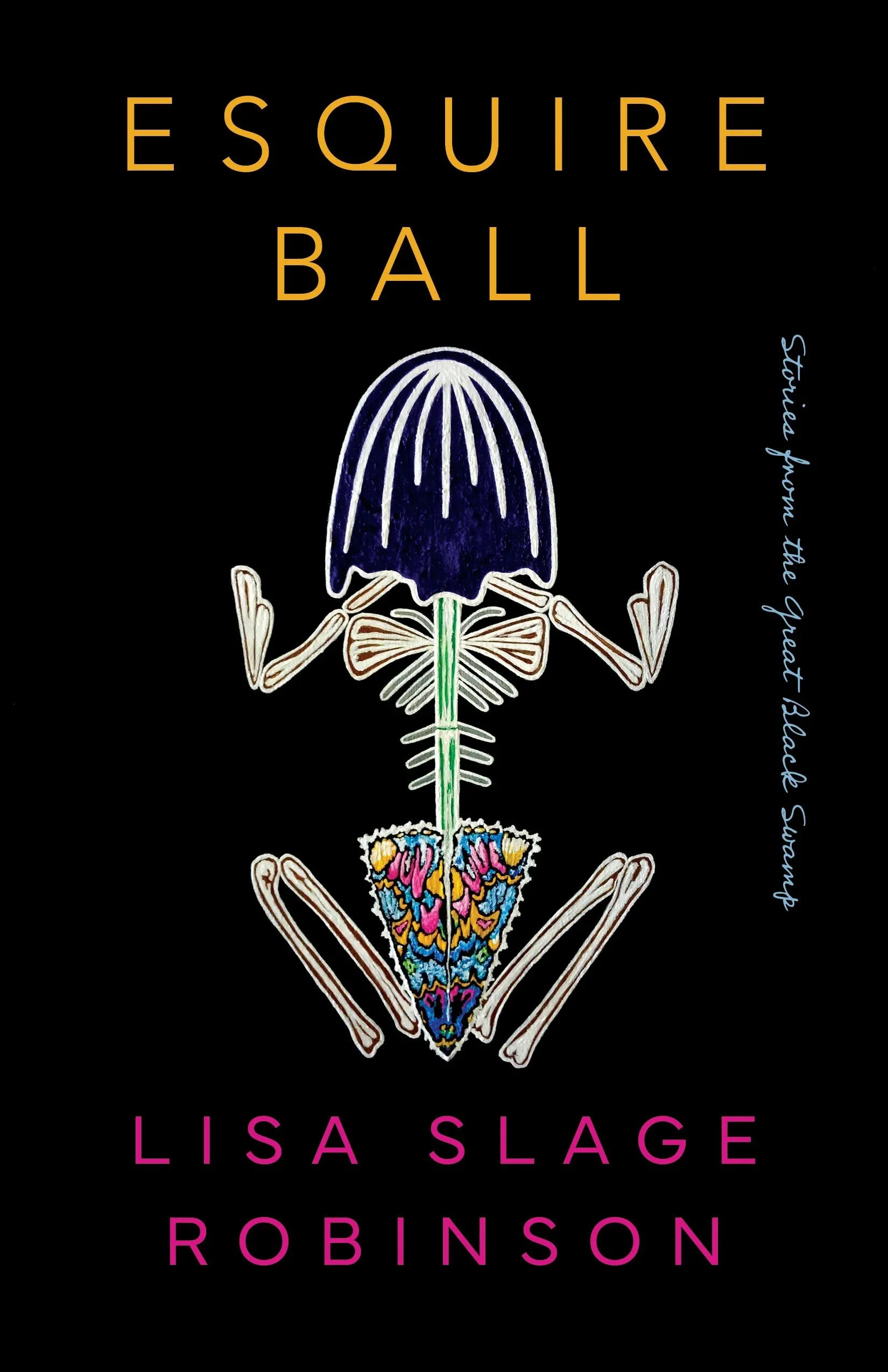

Spotlight: Esquire Ball, Stories from the Great Black Swamp by Lisa Slage Robinson

/Set in Northwest Ohio—a region once known as the Great Black Swamp—the stories in ESQUIRE BALL explore the buried violence of drained and deforested land, where lives are altered by ambition, loss and unexpected revelations. In this surreal terrain, men marry frog wives, a lawyer stalks her client for a keepsake, souls are trapped in farmhouse windows, a teenager drowns in a sea of corn, a woman shares cosmic truths via an otherworldly threesome, and a law student glimpses the future in a museum of medieval torture.

Excerpt

Bird with Lavender Tongue

The girl was a wild little thing, slight with tangled hair, ragged fingernails, and impossibly dirty feet. Pretty doesn’t come to mind but I found her mouth beguiling, its sap-stained corners, the dusting of blue-black soil sprinkled like cookie crumbs on her lips. I told my brother’s wife about her, how the girl wedged high up in an oak tree had pelted me with green acorns that summer I ran the trail at Swann Creek Park. Each loop was only about a mile or so, and I had made up my mind to do six or seven laps before I punched the clock for my shift at the Dairy Mart. As far as my brother was concerned, running was my only talent, my only ticket to college, the only way he and his wife could be released from the burden of me. I generally agreed with his assessment. I had an unforgiveable, lackadaisical nature and a deep aversion to schoolwork. But I could run with abandon. I reveled the burn in my chest and the rhythmic thwap of my Adidas pounding mile after mile.

Otherwise, I was a layabout. I stayed up late watching Johnny Carson on the black and white portable, sipping gin, any which way (up, on the rocks, or dirty with olive juice and a splash of vermouth) and once the TV had forsaken me and all the networks signed off for the night, I reached for one of my mother’s books, of which there were hundreds, and another tumbler or two of gin. In this way, I puzzled together my mother in a way that I couldn’t puzzle math or my brother or our father.

My brother’s wife convinced him to accept what she called my eccentricities brought on by what she believed to be persistent and delayed grief. So he didn’t say a word when he found me lounging in a bubble bath reading a swollen copy of Ayn Rand or lying down in the back seat of my mother’s car, the one that hadn’t crashed, with Silent Spring. But the day my brother came down to breakfast and found me sporting our father’s fishing hat, fishing lures and flies jiggling as I wolfed down the last of the Cap’n Crunch, thumbing through a dog-eared and underlined copy of Jaqueline Susann’s The Love Machine? Now that was something else.

“What the fuck are you reading?” he said. He smacked it out of my hand and proceeded to pound me with his law school hornbooks. Those things were thick and heavy hardcover treatises, nothing like my mother’s paperbacks. He heaved Corbin on Contracts, Prosser on Torts, Laurence Tribe on Con Law. Even Black’s Law Dictionary had a turn. They left welts and later bruises.

Yes, running was my ticket out.

I told my brother’s wife how I was just hitting my stride, soon to be in the zone, where a euphoria better than a boozy haze could be found, where I’d soon be floating rather than racing to the top of the hill—when the first round of insults hit my shoulders, making contact with the bruised places my brother’s justice had administered. “Hey!” I shouted. I picked up a rock, intending to throw it the next time around. It felt good and jagged, authoritative in my fist. But the next time around, I heard laughter, there was no menace in it, just delight. I looked up, salty sweat stinging my eyes, the sun filtered through the leaves obscuring my vision. I looked higher still and saw her, a girl around my age straddling a branch, bare feet swinging, the folds of her white dress aflutter.

I wanted to show off—I ran fast—gathered tokens along the trail and left them at the base of the tree with each passing loop. The jagged rock, a fistful of Queen Anne’s lace and wild snapdragons, a handful of mushrooms, fiddleheads, a salamander. I sang her a song. I pleaded with her to spare my heart. Wouldn’t she please come down?

Still, she refused.

I hadn’t planned to hit her, or hurt her. I just—wanted her. The rotten core of me picked up the rock that I had offered earlier as tribute and hurled it, heard it ricochet off the trunk with a smack. On the final loop, as I crested the hill, I saw a body. It was the girl lying flat on her back, dress askew—exposing one small breast and a hint of her private regions, the proper names for which didn’t readily come to mind. My brain could only summon paperback euphemisms and back-of-the-school-bus vulgarities we boys snickered loudly and often. Her glassy green eyes stared up into the sky.

Certain I had killed her, too dumb to check her pulse or try CPR, I prepared her body for the inevitable. I wept as I arranged her limbs. I plucked leaves and twigs from her dress. Before I covered the porcelain swell of her chest, I extracted a splinter and kissed the angry spot where it had been lodged. I raked my fingers through her auburn hair but it refused to be tamed, it seemed rooted somehow—so I braided a crown with flowers and fiddleheads and wreathed them into a halo on her head.

I thought I should say a prayer or something, but since I didn’t believe in God anymore, I conjured a poem from one of my mother’s books, the one about Xanadu and Kubla Khan.

The dead girl smiled so I lingered. Marveled at the beauty of death because—even in this pretend version—it was lovely and more than I had previously been permitted to see.

I bowed my head and whispered, “Who are you?”

The tree quivered, its limbs sighing with a ribbon of summer breeze. A warbler trilled to the far-off percussion of a woodpecker’s rapid-fire drill.

And then she wrapped her legs around my waist, pulled me toward her, flipped us around, her on top, straddling me. She pinned my arms above my head, leaned in and kissed me, hard then softly, with her dirty mouth. She smelled like juniper and honeysuckle, tasted like spiders and loamy earth. When she finally told me her name, she spoke like a fairy story, sentences riddled in rhyme.

“The trees call me Phoebe,” she said. Her voice mossy, a thick slurry of twigs and bitter berries. A little bird with a lavender tongue. Her pelvis a hot insistent pressure. “I am the guardian of this grove. With the power invested in me,” she said, the full weight of her pressing harder, “I claim you as my consort.” Then she promised she’d share with me the secrets of the universe, what cannot be said in words, all that she had learned from talking to the trees.

I returned to the shade of the great oak every morning that summer. Sometimes, I’d linger for hours hoping to catch a glimpse of her. Sometimes, she’d be waiting for me with a wood nymph’s smile.

After high school graduation. My brother’s wife couldn’t convince my brother to indulge my intention to major in poetry or philosophy.

“I mean, what kind of bullshit is that?” he said.

So I majored in journalism and landed a job with the Toledo Blade. It was a print and pay situation. Ten cents a word. Given my lack of enthusiasm for the kind of assignments awarded to young reporters, (The Peach Section—weddings, funerals, movie reviews, Peach Girl profiles) it wasn’t long before I was evicted from my shitty apartment. I slept in my car for a few weeks before I summoned the courage to ask my brother and his wife if I could return to the fold and crash on their couch. He was working at the law firm by then, hoping to become the firm’s youngest partner. She had quit her job to concentrate on baby making. My brother had responded tenderly the first time (even the second and third time) when she confessed that the life inside her had inexplicably expired. From the sidelines, I watched him cradle her, bring her cups of tea, rub her feet.

But the fourth time, four months in, on the cusp of the big trial, the night before voir dire, she interrupted a meeting with the jury consultant. The news about her incompetent cervix was not received with great compassion. I took her to the clinic, held her hand (despite the doctor’s outraged and ardent objections) while he scraped and suctioned the residual fetal tissue from her womb, while my brother and the jury consultant discussed peremptory challenges and the vulnerabilities of the jury pool.

The procedure didn’t take very long. Afterwards, I drove my brother’s wife home, stopping on the way to buy her sanitary pads and Tylenol at the convenience store. I also bought us a video, potato chips and French Onion dip, Heavenly Hash ice cream and cheap red wine.

I settled her on the sofa with the snacks, wrapped her in an old afghan, and popped The Princess Bride into the VCR. The machine zip, zip, zipped and whined. The screen turned black. I pushed the eject button, releasing the case and loops of videotape tethered to an invisible hand deep inside. I grabbed her spoon, licked off the marshmallowy chocolate, lifted the little door, peered inside the dark chamber and was about to insert the spoon into the VCR’s womb when my brother’s wife yelled, “Stop!”

I thanked her for saving me from certain electrical shock and reached over to pull the plug. But she confessed as she grabbed the spoon back and plunged it into the ice cream tub that she wasn’t saving me. The mangle of tape was just too much for her to bear.

We sat there for a long time—passing the tub and the spoon back and forth. Refilling our glasses. Staring at the speechless TV, divining meaning in its silence.

When we ran out of wine, I went in search of gin. I found a couple of airplane minis stashed behind a battered and yellowed copy of The Little Prince from which I read out loud to her well into the night.

I showed her the illustrations as if I were a kindergarten teacher at story hour. She laughed at the pictures of the snake and the hat and the elephant and the little prince with his yellow scarf flagging. Noted how lucky he was, that prince, to own a rose and three volcanoes. But she soon fell sullen and teary-eyed, turned her face away, her chest heaving. She unscrewed the tiny bottle of Tanqueray and downed it with three determined gulps. “He shouldn’t have left the rose there—all by herself—on that asteroid.” Flicking the tears away, she repositioned herself on the sofa, stretching her legs and settling her feet into my lap. I watched her fingertips trace the circumference of her empty belly in slow sad circles. “Tell me a better story,” she said.

I wanted to peel off her fuzzy striped socks, rub the misery from the arches of her delicate bony feet, wiggle each pearly-pink nail-polished toe. But I didn’t dare. So I told her about the girl but not what happened after.

I told her how the girl lived in the branches under a canopy of flowing gossamer sheers as thin and delicate as bees’ wings. I told her how we picnicked, the food we ate: little cucumber and egg salad sandwiches on buttered white bread with the crust cutoff, biscuits with clover honey and strawberries and cream. And wild concoctions of tonic made of bark and flower buds which we sipped from cups fashioned from the folds of oak leaves. I told her the girl had porcelain skin and copper penny hair that had a habit of braiding with the tree’s roots. And when this happened, the girl’s lips would curl up into a lopsided smile, as if someone had just whispered a joke, a bit of delicious gossip. When she wasn’t tangling with the tree, she preferred the upper reaches of its canopy. She’d tease me, crawl out to the furthest reach of a thin branch that was too heavy for me to traverse—as it would surely break from my weight. My frustration. Her laughter, tiny chimes flirting with the wind.

“And did she ever tell you what the trees said?” my brother’s wife asked.

Not then, not exactly. It would be years later, many years after we first met. I suppressed a grimace, searching for the right words.

“You loved her, didn’t you?” she said playfully, jabbing my thigh with her toes. I wished that I had. I was a boy then. What did I know about love?

“It’s been a long day, you should go to bed,” I said.

“No, not yet.” She arched her back, shifted her hips and sighed, “I’m not sleepy.”

We both knew she was waiting for my brother. Around two-ish, the clink of keys in the porcelain dish in the hallway announced his arrival. He glanced at us, waved his hand dismissing any words of greeting, shook his head, mumbled something about the fuckup who had come to save the day, and slowly climbed the stairs. A few hours later, when my brother’s wife heard him showering, she rose from the sofa, stiff-limbed and shaky, to make him a pot of coffee. She left behind a scarab shaped stain, a mirror image of the blackened ruby blemishing the seat of her grey sweatpants.

In the kitchen, she helped my brother wind his yellow tie into a smart double Windsor knot. She relevéd, up onto her tiptoes, to give him a kiss. But he was distracted by the convention of crows loitering on his brand new sedan. He rushed out the door, waving his hands, cursing at the bloody motherfuckers. But they didn’t budge, just laughed at his passionate outrage, reminding me of the girl in the tree, the last time I saw her, how we parted ways. Red-faced, he marched back into the house, grabbed his keys and suit jacket, gave my sister-in-law a curt peck and said, “Gotta go.” The crows clung to their perches, on the roof and the hood and the side-view mirrors as he backed down the entire length of the driveway. Not until my brother sped away did they condescend to spread their wings and take flight.

Excerpted from ESQUIRE BALL: Stories from the Great Black Swamp, by Lisa Slage Robinson (Black Lawrence Press; February 10, 2026)

Buy on Amazon Kindle | Paperback | Bookshop.org

About the Author

Lisa Slage Robinson serves on the Board of Directors for Autumn House Press. Named a finalist for Midwest Review’s Great Midwest Fiction Contest, her work appears in Iron Horse Literary Review, Smokelong Quarterly, The Adroit Journal, PRISM, Atticus Review, Storm Cellar, Necessary Fiction, Lit Pub, Meat for Tea and elsewhere. A former litigator and corporate attorney, she practiced law in the United States and Canada. Born and raised in Ohio, she lives in Pittsburgh with her husband and keeps the lights on for their daughters. You can visit her at lisaslagerobinson.com.

Connect:

Website: https://lisaslagerobinson.com/

Instagram: @slagerobinson